Introduction

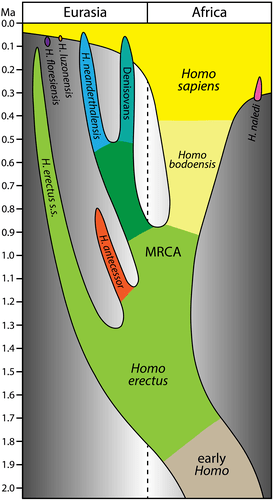

Throughout the history of our evolution, few times have confused anthropologists more than the middle to late Pleistocene epoch. This time, from about 1 million years ago to 10,000 years ago, saw the emergence of our own species, along with our closest relatives, Neanderthals and the Denisovans. Sites from throughout Africa and into Europe give hints to our common ancestor with these other species, along with the origins of our own species, but perplexing morphologies in the fossil specimens make this time very confusing. Because of this, anthropologists have given this time the nickname, the ‘Muddle in the Middle’.

From this time at the end of the Pleistocene, there are plenty of fossil hominins. Fossils have been found all throughout Africa, Europe, and even as far into Asia. It is not a lack of fossils that makes this period of time confusing, rather the morphologies seen within the fossils. Many fossils have very similar traits to one another, making it difficult to decipher what specimens belong to what species. To make it worse, the geography and locations of these fossils makes it more confusing.

This time raises 3 main questions. First off, who was the common ancestor of us and our evolutionary cousins? Secondly, where did the Neanderthals even come from? And thirdly, and perhaps most important, where did we, Homo sapiens, come from? Though there is certainly no clear picture (at least, not yet), by examining all the fossils and evidence, we can get a decent understanding of what was happening in the infamous ‘Muddle in the Middle’.

Who was our Common Ancestor?

There are several species which could possibly be the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) between us and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). The most commonly accepted species is Homo heidelbergensis, but there is little agreement on what fossils are and are not this species.

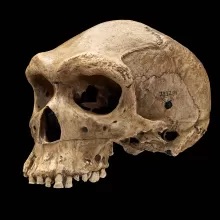

Homo heidelbergensis is a mid-late Pleistocene hominin which lived about 600,000-300,000 years ago. This species shared several traits with modern humans (Homo sapiens), but was also very different. This species had larger jaws, teeth and face, particularly in terms of their brow ridges and frontal sinus. Virtual reconstructions of what the MRCA should look like match the morphology seen in Homo heidelbergensis, giving more support to the idea that this species, or something like it, is the common ancestor.

Fossils attributed to this species are found all throughout Africa and Europe. Specimens of Homo heidelbergensis from Africa, such as the Broken Hill skull (Kabwe 1) have been placed under the species name “Homo rhodesiensis”, though this taxa is not typically used. Other fossils from Europe may represent European H. heidelbergensis, but also might represent early, or ‘proto’ Neanderthals. One site in particular, in Spain, has provided many fossils from and can give great insight to understanding this mysterious time.

Found in Atapuerca, Spain, the Sima de los Huesos (“pit of bones”) site possesses many fossil hominins attributed to Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis. This site contains 12 stratolithographic chambers, only one of which (LU-6), contains hominin remains, along with other animal remains, such as bears (Family: Ursidae).

In this site, close to 8,000 fossil hominins have been found and excavated, making up roughly 30 individuals. Many of the specimens, such as the cranial specimen Atapuerca 5, have been attributed to Homo heidelbergensis, but resemble Neanderthals greatly in their morphology. This is seen especially in the dental remains from this site, of which there are over 30.

These teeth give great insight to the origins of Neanderthals. If these teeth do indeed belong to Homo heidelbergensis, it may support the idea that this species was only ancestral to Neanderthals, and may represent an early Neanderthal lineage.

Another species, also from Spain, may represent the common ancestor as well, Homo antecessor.

Homo antecessor is a species of late Pleistocene hominin which lived in Spain from 1.2 million-800,000 years ago. Found in Gran Dolina Cave, in Atapuerca, this species is the oldest known hominin from western and central Europe, giving clues to when humans first reached this area. This species lines up with the idea that humans migrated to Europe in several sporadic migrations/waves, with some of the oldest evidence of human habitation from Europe being stone tools dating to 1.2 million years ago. These tools suggest that humans adapted to the new European environments by improving their tools.

Homo antecessor is sometimes considered to be early European Homo heidelbergensis, and was once considered to be the common ancestor of us and Neanderthals, but it is no longer typically thought to be that. Instead, this species is thought to be a sister species to H. heidelbergensis descending from Homo ergaster in Africa.

Throughout the years, many of the Pleistocene hominin fossils from across Europe and Africa and even into Asia have been given different species names, such as Homo capanensis, Homo mauritanicus, and Homo helmei. However, recently, a new species was suggested in an attempt to clear up the muddle in the middle.

Homo bodoensis

Named Homo bodoensis, this new species would have a geographical range of parts of Africa and Europe, possibly representing the MRCA. Homo bodoesnsis is composed of African specimens of Homo heidelbergensis along with some European specimens, while other European specimens which more closely resemble Neanderthals, such as the ones from Sima de los Huesos, were grouped in under Homo neanderthalensis, as early Neanderthals.

Homo bodoensis is not widely accepted however, as many anthropologists believe that this could have been done but still under Homo heidelbergensis, saying that there is no need for an entirely new species.

No matter what species name you use, the fossils clearly show the origins of Neanderthals and our shared common ancestor with them. However, it does little for the origins of our own species, Homo sapiens.

Origins of Homo sapiens

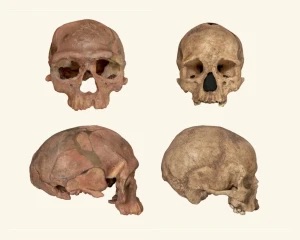

The origins of our own lineage is one of the most interesting and important parts of this topic. Our species most likely arose out of Africa, though some have suggested we evolved in southwest Asia. Early fossils of Homo sapiens from Africa, though rare, show a lack of mosaic traits which is what would be expected in the LCA. Fossils such as Omo Kibish 1, Herto 1, and Herto 2, give further support to the idea that we arose in Africa, as they share a significant amount of derived traits with modern humans, and are likely some of the earliest known specimens of our own species.

Fossils of early Homo sapiens have been found from all throughout Africa, such as Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, and Florisbad, in South Africa. The oldest fossil of our species, known as Jebel Irhoud, suggests that Homo sapiens most likely evolved around 300,000 years ago.

The earliest Homo sapiens are referred to as ‘anatomically archaic’, and were morphologically different compared to anatomically modern Homo sapiens. They had larger brow ridges, a more extended skull, and overall looked more like earlier species such as Neanderthals. Archaic Homo sapiens existed from 300,000 to 160,000 years ago, when modern Homo sapiens took over. It wasn’t a sudden and quick transition however, as fossils show a chronological overlapping range in the variation of the two.

The Full Story

600,000 years ago in southern Africa, a new hominin species arose from Homo ergaster (African Homo erectus). This species, known as Homo heidelbergensis/Homo bodoensis, possessed many ancestral traits, such as a large extended skull, large teeth, large brow ridges, and a large frontal sinus, but also possessed with many derived traits, such as a more orthognathic face and a large frontal cortex.

One population of this new species migrated out of Africa, where it encountered another species which also evolved from Homo ergaster, Homo antecessor, in Spain. Populations of this group out of Africa stayed in Europe, where they would give rise to Neanderthals, while other populations would move farther east, and would become our other cousins, the Denisovans.

Homo heidelbergensis which remained in Africa would give rise to our own species, Homo sapiens. We would spread throughout Africa, then throughout the world, where we would encounter, interact with, breed with, and live with other human species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, until, by 40,000 years ago, we were the only ones left.

Conclusion

The story of our evolution is one of the most extensively researched fields of science. The combination of fossil and genetic evidence gives a great understanding of our evolutionary past, but it isn’t always so clear. The mid-late Pleistocene is one such time. There are many hominin fossils from this time, but the confusing and mixed morphology makes it very difficult to identify and classify them into different species. Fossils from the Sima de los Huesos site in Spain are especially confusing.

Many different species names have been proposed for certain fossils to clear things up, such as Homo heidelbergensis, Homo bodoensis, Homo capanensis, Homo mauritanicus, and Homo helmei, but there is little agreement on what species are valid or not, and this usually only confuses things more. Further research and discoveries, such as new fossils and genetic evidence are our best hope to resolve this confusing time.

Sources

- Fran, Dorey. “Homo heidelbergensis”. The Australian Museum, 28-06-21, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-heidelbergensis/

- Godhino, M. R., Fitton, C. L., Toro-Ibacache, V., Stringer, B. C., Lacruz, S. R., Bromage, G. T., O’Higgins, P. (2018). The biting performance of Homo sapiens and Homo heidelbergensis. Journal of Human Evolution, 118, 56-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.02.010

- Godhino, M. R., O’Higgins, P. (2017). The biomechanical significance of the frontal sinus in Kabwe 1 (Homo heidelbergensis). Journal of Human Evolution, 114, 141-153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.10.007

- Stringer, C. (2012). The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908). Evolutionary Anthropology, 21(3), 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21311

- Perner, J., Esken, F. (2015). Evolution of human cooperation in Homo heidelbergensis: Teleology versus mentalism. Developmental Review, 38, 69-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2015.07.005

- “Kabwe 1”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/kabwe-1

- Mounier, A., Marchal, F., Condemi, S. (2009). Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible. Journal of Human Evolution, 56(3), 219-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.12.006

- Czarnetzki, A., Jakob, T., Pusch, M. C. (2003). Paleopathological and variant conditions of the Homo heidelbergensis type specimen (Mauer, Germany). Journal of Human Evolution. 44(4), 479-495, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2484(03)00029-0

- “Florisbad”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/florisbad

- Curnoe, D., Brink, J. (2010). Evidence of pathological conditions in the Florisbad cranium. Journal of Human Evolution, 59(5), 504-513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.06.003

- Gracia-Téllez, A., Arsuaga, L, J., Martínez, I., Martín-Francés, L., Martinón-Torres, M., Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Bonmatí, A., Lira, J. (2012). Orofacial pathology in Homo heidelbergensis: The case of Skull 5 from the Sima de los Huesos site (Atapuerca, Spain). Quaternary International, 295(8), 83-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.005

- Sala, N., Pantoja-Pérez, A., Arsuaga, L. J., Pablos, A., Martínez, I. (2016). The Sima de los Huesos Crania: Analysis of the cranial breakage patterns. Journal of Archaeological Science, 72, 25-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.06.001

- Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Martínez I., Gracia-Téllez, A., Martinón-Torres, M., Arsuaga, L. J. (2020). The Sima de los Huesos Middle Pleistocene hominin site (Burgos, Spain). Estimation of the Number of Individuals. The Anatomical Record, 304(7), 1463-1477. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24551

- Carretero, J., García-González, R., Rodríguez, L., Arsuaga, L. J. (2023). Main anatomical characteristics of the hominin fossil humeri from the Sima de los Huesos Middle Pleistocene site, Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain: An update. The Anatomical Record. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.25194

- Martinón-Torres, M., Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Gómez-Robles, A., Prado-Simón, L., Arsuaga, L. J. (2011). Morphological description and comparison of the dental remains from Atapeurca-Sima de los Huersos site (Spain). Journal of Human Evolution, 62(1), 7-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.08.007

- Martínez, I., Arsuaga, L. J., Quam, R., Carretero, M. J., Gracia, A., Rodríguez, L. (2007). Human hyoid bones from the middle Pleistocene site of the Sima de los Huesos (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). Journal of Human Evolution. 54(1), 118-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.07.006

- Dorey, Fran. “Homo antecessor”. The Australian Museum, 17-12-19, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-antecessor/

- Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Martinón-Torres, M., Martín-Francés, L., Modesto-Mata, M., Martínez-de-Pinillos, M., García, C., Carbonell, E. (2017). Homo antecessor: The state of the art eighteen years later. Quaternary International, 433 (A)(17), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.049

- Barsky, D., Garcia, J., Martínez, K., Sala, R., Zaidner, Y., Carbonell, E, Toro-Moyano, I. (2013). Flake modification in European Early and Early-Middle Pleistocene stone tool assemblages. Quaternary International, 316(6), 140-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.05.024

- Harvati, K., Reyes-Centeno, H. (2022). Evolution of Homo in the Middle and Late Pleistocene. Journal of Human Evolution, 173, 103279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103279

- Mallegni, F., Carnieri, E., Bisconti, M., Tartarelli, G., Ricci, S., Biddittu, I., Segre, A. (2003). Homo cepranensis sp. nov. and the evolution of African-European Middle Pleistocene hominids. Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2(2), 153-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1631-0683(03)00015-0

- Roksandic, M., Radović, P., Wu, X., Bae, J. C. (2022). Resolving the ‘Muddle in the Middle’: The case for Homo bodoensis sp. nov. Evolutionary Anthropology. 31(1), 20-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21929

- “Bodo”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program. 08-30-22, https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/bodo

- Dorey, Fran. “Homo neanderthalensis-The Neanderthals”. The Australian Museum, 28-06-21. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-neanderthalensis/

- Stringer, C. (2016). The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 371(1698). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0237

- Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Martinón-Torres, M. (2022). Quaternary International, 634(10), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.08.001

- Dorey, Fran. “Homo sapiens-modern humans”. The Australian Museum, 16-10-20, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-sapiens-modern-humans/

- Callaway, E. (2017). Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species’ history. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2017.22114

- Dorey, Fran. “The Denisovans”. The Australian Museum, 20-04-20, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/the-denisovans/

I think this would benefit from referencing two key bits of evidence on the European side. Re Antecessor, note Welker et al 2020. Proteomic evidence that Antecessor is a close relative of the ancestor of the Sapien/Neanderthal/Denisovan clade. Re Sima de los Huesos, DNA recovered by Meyer et al 2016 indicates nuclear DNA closer to Neanderthals than Denisovan, so they should be on Neanderthal line after Denisovan / Neanderthal split. But to add to any muddle, mtDNA from there is closer to Denisovan than Neanderthal. They tentatively suggest later Neanderthal mtDNA came from another line.

LikeLike

Unfortunately, I do not have access to those papers. I came across the Homo antecessor paper when doing research for this article, but I couldn’t do much with it. I do bring up from different sources however that antecessor seems to be a sister species to H. heidelbergensis, which would make it closely related to the clade with Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, etc. I was unaware of the second paper you brought up, but it is certainly very interesting. I may find other ways to get the information from that paper so I can update this article when I find time. Thank you for bringing this to my attention.

LikeLike