Introduction

November 24th, 1974, exactly 49 years ago today, the world of paleoanthropology was changed forever. On this day, Donald Joahanson and his team discovered perhaps the most famous specimen of our evolutionary lineage, Lucy.

Lucy’s fame comes from the fact that she was the first of her species (Australopithecus afarensis), not because she’s the best specimen of this species, but for her time, she was very important, and would give us the first glimpse of the lives and biology of our ancestors.

Lucy’s Discovery

Lucy was discovered in 1974 in Hadar Ethiopia, by a team of paleoanthropologists made up of Donald Johanson, Tom Gray, Maurice Taieb, Alemayehu Asfaw, along with others. Johanson, who was 31 at the time, had recently gained his Ph.D and was a professor in Cleveland, Ohio. He had been to Ethiopia twice before, and even discovered a hominin knee joint on his second trip, the first hominin remains ever uncovered in the region. This discovery gave him hope for new discoveries this time.

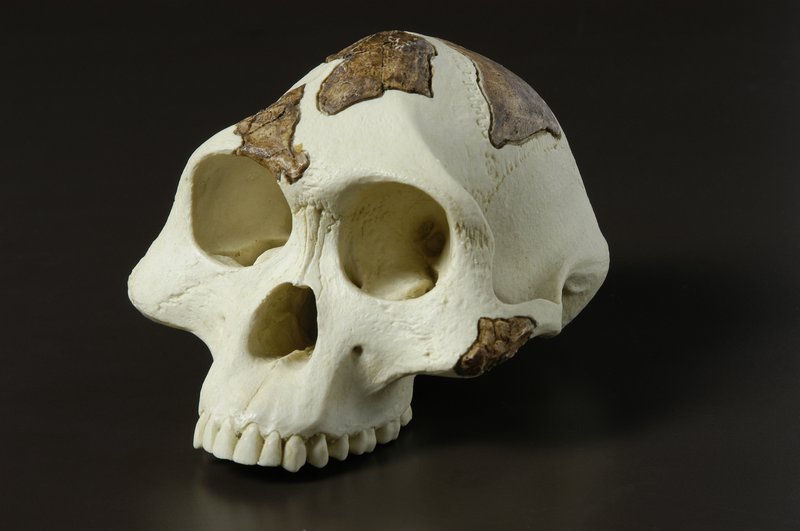

Just as he hoped, he had more luck in 1974, when he discovered a partial skeleton of an australopith. He first spotted the proximal region of the ulna bone in the forearm. After some work, the team eventually uncovered many other fossils, including cranial fragments, a mandible, some ribs, vertebrae, both arms, parts of her pelvis (including her sacrum and innominate bone), and parts of her legs and feet. All the remains would make up about 40% of the full skeleton.

The specimen would be given the nickname of ‘Lucy’, named after the at the time popular Beatles song, “Lucy and the Sky of Diamonds”. She would be given the Ethiopian name Dinknesh, which is Amharic for “you are marvelous”. The fossils would be dated to about 3.2 million years old, and would be given the new species name, Australopithecus afarensis, meaning southern ape of Afar, named after the Afar region of Ethiopia she was discovered in.

Lucy’s Significance

Though Lucy wasn’t the first of the genus Australopithecus discovered, that honor goes to the Taung Child which was discovered 40 years earlier in 1924 by Raymond Dart, belonging to the species Australopithecus africanus, she was the first of the species Australopithecus afarensis to be discovered.

Since her discovery, several hundred other fossils have been found, making up many individuals, including Kadanuumuu, Selam, and the first family. Research from these fossils show that this species lived from about 3.9-2.8 mya, and lived throughout eastern Africa.

What we Can Learn from Lucy

Lucy’s size made Johanson believe that she was female, as in most primates, the females are much shorter. Computer reconstructions of Lucy’s femur gives it a length of of 277 mm, very close to previous estimates. Relating this to the rest of her body, Lucy seemed to have been about 104-106 cm tall, while males stood about 150 cm tall. This couldn’t have been because of her age however, as all her adult teeth had grown in by the time of her death.There has been some debate on Lucy’s sex, such as Häusler and Schmid (1995), but the larger consensus is that she was female. Along with her femur, Lucy also has a well preserved pelvis.

Lucy’s pelvis consists of a sacrum and innominate bone. Her sacrum had 5 fused sacral vertebrae just like modern humans, sharing the same morphology as well, such as an inferiorly-projecting cornua and a kidney-shaped inferior body articular surface. This morphology is also found in other related species, like Australopithecus sediba.

Compared to a chimpanzee and human pelvis, Lucy’s pelvis was more platypelloid, or flat. This has two implications for Australopithecus, 1. Bipedal locomotion would be much easier for them, and 2. Birth for this species would be slow and difficult, due to the pelvis being more narrow. Moving up from the pelvis, her vertebrae also hold some significance.

Lucy was found with 9 vertebrae. One vertebrae was uniquely worn and of a different texture however, and would later be reclassified as a vertebrae of Theropithecus darti, a large extinct species of modern Geladas, an old world monkey. This resulted in a reexamination of Lucy’s fossils, showing that the rest of her fossils did indeed belong to her.

This resulted in heavy scrutiny being placed on the whole hominin fossil record to make sure all the fossils were valid, ultimately being great for paleoanthropology. Overall, Lucy’s vertebrae were very human-like, and give some clues to how she walked, but aren’t useful for very much.

Lucy’s arms were very long, and had muscle attachment sites on her humerus, giving her very powerful arms great for climbing in trees. Lucy’s forearms also had the capacity for great elbow flexion, similar to chimpanzees, and had elbow extension similar to orangutans. This shows that Lucy was a great climber and certainly still spent time in the trees, but she was still clearly well adapted for terrestrial bipedalism.

Her femur was intermediate between chimpanzees and humans. Though her arms were well adapted for arboreal locomotion, her legs were well adapted to walking, with cortical thickness in the femoral neck which is useful for weight bearing. Digital muscular reconstructions of Lucy also show that she could walk bipedally. 36 muscles were recreated. The muscles in the leg were much larger than they are in humans, with the muscles in the thigh making up 74% of the mass of the leg compared to the 50% in humans.

These muscles would have made it very easy to walk on her two legs efficiently. Her legs and pelvis would have given her great ability to walk on her two legs, though she would still spend time in the trees, likely more at night to avoid nocturnal predators.

Lucy’s Death

The time Lucy spent in the trees may have ultimately been her demise. CT scans of Lucy’s fossils that were originally meant to study her locomotion showed impacted fractures and patterns of collapse. These fractures resembled that of a four-part proximal humeral fracture, which occurs when the head of the humerus is shoved into the shoulder joint, an event that usually happens when you brace yourself with your arms during a large fall or during a car crash. This suggested to the researchers that Lucy fell from some height, such as a tree.

Similar fractures were found throughout her body, in her ankle, knee, pelvis, and ribs. The researchers calculated that fractures like this would be the result of fall from a four story height at about 59 kilometers per hour. The fractures also had no sign of healing, suggesting that she was killed quickly by the supposed fall. Not everyone agrees with this idea however.

Others have suggested that the fractures were results of later geological processes after death. The fractures found in Lucy are also found in other animal fossils from the area, including the ones that would be spending no time in the trees at all, like antelope, gazelles, elephants, rhinos, and giraffes. This makes Lucy’s fall more controversial, and the true cause of her death unknown.

Conclusion

Though Lucy is by no means the best example of human evolution uncovered so far, she can still give us great information about our ancestors. From her size, the way she walked, her life, and her death, this 3.2 million year old australopith is still very significant, and was discovered exactly 49 years ago today.

Sources

- Schrein, C. M. (2015) Lucy: A marvelous specimen. Nature Education Knowledge 6(7):2. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/lucy-a-marvelous-specimen-135716086/

- “AL 288-1”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 06-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/al-288-1

- “Taung Child”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/taung-child

- Dorey, Fran. “Australopithecus afarensis”. The Australian Museum, 14-05-21.https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/australopithecus-afarensis/

- Sylvester, D. A., Merkl, C. B., Mahfouz, R. M. (2008). Assessing A.L. 288-1 femur length using computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction. Journal of Human Evolution, 55(4), 665-671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.05.019

- Tague, G. R., Lovejoy, O. C. (1998). AL 288-1–Lucy or Lucifer: gender confusion in the Pliocene. Journal of Human Evolution, 35(1), 75-94. 10.1006/jhev.1998.0223

- Russo, A. G., Williams, A. S. (2014). “Lucy” (A.L. 288-1) had five sacral vertebrae. American Journal of Biological Anthropology. 156(2), 295-303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22642

- Rak, Y. (1991). Lucy’s pelvic anatomy: its role in bipedal gait. Journal of Human Evolution, 20(4), 283-290. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(91)90011-J

- Tague, G. R., Loveyjoy, O. C. (1986). The obstetric pelvis of A.L. 288-1 (Lucy). Journal of Human Evolution, 15(4), 237-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2484(86)80052-5

- Meyer, R. M., Williams, A. S., Smith, P. M., Sawyer, J. G. (2015). Lucy’s back: Reassessment of fossils associated with the A.L. 288-1 vertebral column. Journal of Human Evolution, 85, 174-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.05.007

- van Hilten, G. L. (2015). Why Lucy’s baboon bone is great for science (and evolution theory). Elsevier Connect, https://www.elsevier.com/connect/why-lucys-baboon-bone-is-great-for-science-and-evolution-theory

- Ibáñez-Gimeno, P. Manyosa, J., Galtés, I., Jordana, X., Moyà-Soyà, S., Malgosa, A. (2017). Forearm pronation efficiency in A.L. 288-1 (Australopithecus afarensis) and MH2 (Australopithecus sediba): Insights into their locomotor and manipulative habits. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 164(4), 788-800. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23319

- Ruff, B. C., Burgess, L. M., Ketcham, A. R., Kappelman, J. (2016). Limb Bone Structural Proportions and Locomotor Behavior in A.L. 288-1 (“Lucy”). PLoS ONE, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166095

- First hominin muscle reconstruction shows 3.2 million-year-old ‘Lucy’ could stand as erect as we do. Phys.org, 07-13-23. https://phys.org/news/2023-06-hominin-muscle-reconstruction-million-year-old-lucy.html

- Gibbons, Ann. “Did famed human ancestor ‘Lucy’ fall to her death?” Science, 08-29-16. https://www.science.org/content/article/did-famed-human-ancestor-lucy-fall-her-death