Introduction

Throughout the history of our evolution, there have been many different things that have shaped us into the animals we are today. From mutations to selection pressures, there are many aspects of our story that are crucial for why we are the way that we are, both behaviorally and physically. This article is about the latter.

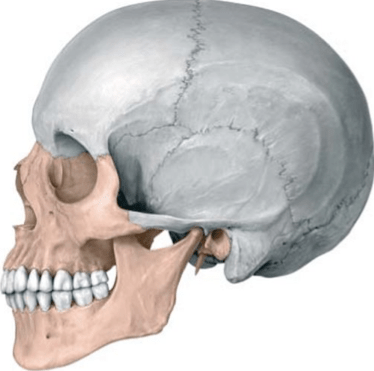

Despite being so closely related to our ape cousins, we physically look quite different in a few ways, especially in our skulls. The other apes, especially the great apes, have very large projecting (prognathic) faces, large brow ridges, larger teeth (especially in the canine teeth), and especially, small brains. Humans however, have flat faces, no brow ridges, small mouths and teeth, and very large brains, the complete opposite. What little genetic difference we have with chimpanzees makes up for all these differences.

There is one overarching reason for this, why we look so different from the other apes despite being so closely related to them, and it requires very little genetic difference. It is called neoteny.

What is Neoteny?

Neoteny is a biological phenomena that has been observed in many different animals, including, it seems, humans.

Neoteny is broadly a form of heterochrony, which is a change in the timing of growth stages in an organism. More specifically, neoteny is a form of paedomorphism, which basically means to have a more juvenile-like appearance. Neoteny specifically is the retention of juvenile traits into adulthood. This usually happens when a mutation causes sexual maturation to occur sooner, when the individual is phenotypically younger. That specific form of neoteny is called paedogenesis. Neoteny is a form of paedomorphism, which is a form of heterochrony.

Neoteny can be very important for evolutionary changes, as if the retention of a certain trait is beneficial, it’ll be passed down, causing great evolutionary changes. Ontogeny is also another important topic for understanding neoteny.

Ontogeny is the development of an organism throughout its life. As neoteny is the slowing of development, ontogeny is important to understand when discussing this topic.

Examples of Neoteny

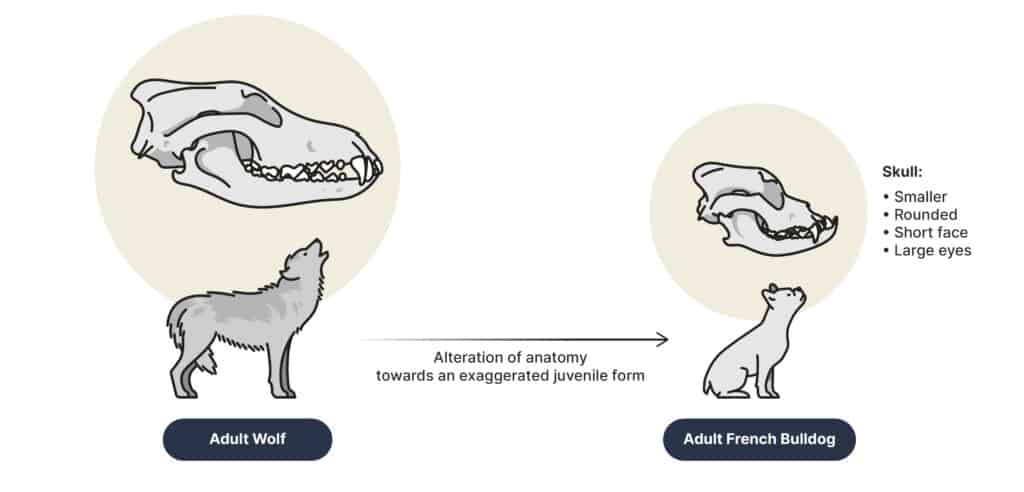

There are many examples of neoteny in animals. Many dog breeds have been selectively bred to be more neotenic. Younger wolves are more social and friendly, making them better household pets, rather than more aggressive guarding and hunting dogs like they were originally domesticated for. This resulted in humans selecting for wolves with more puppy-like behaviors.

Physical neotenous traits were also selected for. Neotenous traits seen in some dog breeds include softer fur, rounder bodies and heads, larger eyes, and floppy ears.These traits are often seen as cuter and friendlier, making them more popular among dog owners. Unfortunately however, these traits are often unhealthy for the dogs, as many have congenital issues, such as brachycephalic skulls, making breathing difficult.

Dogs with these neotenous traits include breeds like chihuahuas and pugs. Dogs were artificially selected for, but there are many natural examples.

Neoteny is also seen as the reason why naked mole rats (Heterocephalus glaber) have such longer lifespans.

While some rodents, like mice, have an average life span of 3 years, naked mole rats can have life spans of up to 30 years. Neotenic traits in these rats include a lower body rate, lack of hair, prolonged gestation, longer times to reach maturity, greater percentage of reproductive success, the absence of a scrotum, a reduced vomeronasal organ, etc. Very few other rodents have these same traits into adulthood.

At birth, naked mole rat brains are much more developed than other rodents as well, and are more alike that of newborn primates. Despite this, these rats take much longer for their brains to mature, taking 4 times longer than average for other rodents. This is a sign of increased neoteny in the brains of these rats.

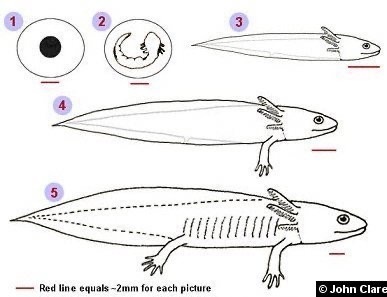

Another good example of neoteny is the mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum).

Axolotls are one of few amphibians that don’t undergo metamorphosis. Because of this, they retain many juvenile traits throughout their lives. One of the most outstanding traits is external gills, one of their most distinguishing traits.

This paedomorphosis is a result of low activity in the hypothalamo-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. The pituitary hormone thyrotropin (TSH) is capable of inducing metamorphosis in axolotls, so all functions of the HPT axis (metabolism and stress responses, etc.) below the pituitary level are functional, except this TSH release.

Neoteny in Humans

There are many examples of neoteny in humans as well, which have had big impacts on our own evolution. Neoteny, especially, is common in our brains. Because of neoteny, our brains take much more time to develop, allowing us to learn much more as we develop. This gives us time to learn more complex behaviors and learn from environmental cues. Extended development in the brain is primarily due to mutations on important developmental genes in the brain.

The slowing of the development of the amygdala-medial PFC (prefrontal cortex) allowed for more time for children and parents to bond. This part of the brain is important for emotional maturity, in behaviors like attention, learning, modulation, and prediction, so extending its development is very useful.

When compared to the brains of other primates, specifically chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and monkeys like rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), humans have much more extended brain development due to this.

When the human variant of the MCPH1 gene, another important gene in brain development, was placed into rhesus macaques, the monkeys experienced greatly delayed brain development, and subsequently exhibited better short-term memory and shorter reaction time when compared to unaltered monkeys, just like what is seen in humans. This shows that the human variants of these genes, which are important for our memory and reaction time, have been greatly changed in our lineage compared to our cousins.

Other genes that control brain regulation, such as RBFOX1, an important hub gene in brain development, are very different from rhesus macaques, showing just how much the human brain has changed in terms of development.

In total, about 7,958 genes related to brain development have been compared between humans and other primates. About half of these genes possess delay in development in humans. Out of 299 of those genes, 40% are even expressed later in our lives than in other primates. This delayed maturation of the brain also has behavioral impacts.

With a larger, more mature, more self aware brain, human social interactions have become much more complex. This may have increased levels of shyness, both fearful and self-conscious shyness.

There’s another neotenous change in humans that is important for human brain development, but rather than the development itself, it’s important for the size of human brains.

Compared to other apes, humans have much smaller jaw muscles and larger brains. This is the opposite in our ape cousins. However, as juveniles, other apes have larger brains and weak jaw muscles, just like humans. This changes greatly as the other apes develop throughout their lives, but it remains this way in humans. This is due partly to a single mutation on one important gene, MYH16.

The MYH16 Gene

MYH16 is a gene found in mammals, but specifically is used in the temporalis and masseter muscles in primates, muscles that are important for chewing.This gene codes for a myosin heavy chain protein, an important protein for muscle contractions in the jaw muscles.

Though this reduced our chewing muscles and therefore our jaw size, it allowed for an increase in brain growth (encephalization), and was therefore beneficial. In humans, this gene has been converted into a pseudogene due to a two nucleotide deletion mutation, hindering the production of the MYH protein, and reducing our chewing muscles. Though this reduced our chewing muscles and therefore our jaw size, it allowed for an increase in brain growth (encephalization), and was therefore beneficial.

Because humans are such social animals, having a larger and more mature brain is very beneficial. We traded our brains for our brawns. This is known as the “less-is-more” hypothesis, having less chewing muscles is more beneficial.

This mutation would have occurred anywhere from around 5.3-2.4 million years ago, likely closer to the latter. It occurred after the split between chimpanzees and humans, but before the split between modern humans and Neanderthals.

This is why chimpanzees and humans look so different in their skulls, despite both being more closely related to each other than either is to a gorilla, because a single mutation alters the growth of chewing muscles in humans, allowing for a larger brain. The roughly 1% genetic difference between chimpanzees and humans is a big difference, partially due to this mutation in this singular gene.

This is neotenous as smaller chewing muscles and larger brains are present in the juvenile forms of all apes, but goes away in all but humans, where it is retained. This is where ontogeny comes in.

Human and Ape Ontogeny

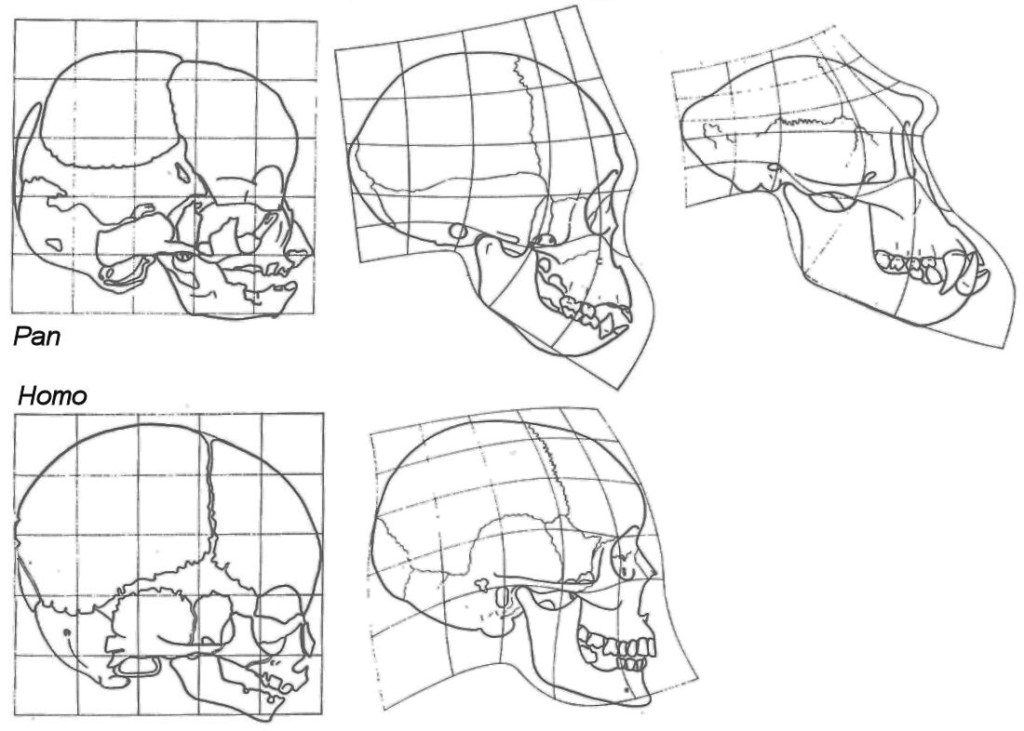

Humans are most similar to the other apes as fetuses, and their skull shape soon begins diverging slowly after birth. Some of these changes diverge at the same rate, while other traits diverge at different times and at different rates.

Some of the biggest changes during ontogenetic development are in the face. Other, non-human apes obtain a larger, more prognathic face, larger teeth (especially in the canine teeth), and a smaller brain. Other important changes include changes in the basicranium, specifically in the foramen magnum. This is important for the locomotion of the animals later in life. These changes are in the neuro and splanchnocranium, the two major portions of the skull.

The splanchnocranium succeeds the neurocranium in the development of the endocranium (the inside of the skull). These changes occur at similar rates in other apes, but are very different in humans, though some variation does exist. Because our brain development is so different from the other apes, there are also other ontogenetic changes in the human endocranium, although ontogeny isn’t the only reason for this.

The brains of postnatal humans begin growing very rapidly. By year one, the brain is 70% the adult size, and by year 6, it’s 90-95% its adult size. Due to the smaller sizes of the brains of other apes, this is very different in them. Humans have an increase in endocranial flexion (pushed forward occipital bones) compared to other apes as well, which is important for some of the other ontogenetic between humans and apes. Cranial flexion also helps with spatial packing of our larger brains, along with aiding in bipedal locomotion.

Some major endocranial changes we know have occurred very recently in our species, as early fossils of our species, like the Herto cranium, lack them, showing that they’re very new traits. The Herto skulls, despite being only about 160,000 years old, have a very different endocranial shape from modern Homo sapiens, though the brains were about the same size.

Due to all these changes during development, the skulls of adult humans are closest to the skulls of juvenile chimpanzees, aside from the growth of the teeth.

The fossils of juvenile australopiths, like the taung and dikika child, are important for tracking these cranial changes in the human lineage. There are also examples of different ontogeny in other places besides the skull. One good example is in the spine, specifically the thoracolumbar region.

The spine anatomy in apes is very diverse, mainly due to posture and locomotion. Because of the different vertebrae throughout the apes, the ontogeny of the vertebrae is unique. Not a lot is known about the development of the vertebrae, but comparing the vertebrae of juvenile humans, apes, and extinct hominins like Australopithecus and Homo erectus.The vertebrae of humans and chimpanzees are more alike than they are to gorillas and orangutans.

Also in chimps and humans, the development of the vertebrae develop much more than in the other apes. In humans however, our development finishes much quicker. This is exactly what is seen in extinct hominin species. Though the vertebrae of humans and chimpanzees are very similar, one big change is humans gain a longer lumber column, which aids in our upright posture. Ontogeny is also present farther down the body in the femora.

Even though chimpanzees and gorillas walk very similarly, the ontogeny of their femora is still different in multiple ways. The basic development of the femora in primates is the same, but varies in slight details. Humans differ from this the most, with longer angled femora, also for bipedal locomotion. Overall, humans most resemble our ape cousins in most aspects of the body when they’re juveniles, but this quickly changes as the other apes grow, while humans stay relatively the same.

Conclusion

Evolution is run primarily by random mutation, which is then selected for by non-random mutation. Depending on what the mutation does, and the environment of the organism, the change will either be selected for or selected against. Humans, up until very recently, have been exposed to countless selection pressures. As a very social species, having a mutation that allows for extended brain development and an overall larger brain would be very quickly selected for. Neoteny is one of the many ways this occurred.

Neoteny allowed us to trade our larger mouths and stronger bites for larger brains and extended brain development. This is why humans look so different from our closest living relatives. There have been a few small genetic changes in a very small portion of DNA that drastically altered our lives, biology, and appearance, showing just how significant small genetic changes can be.

Sources

- “Neoteny”. Ishinobu, 02-17-20. https://ishinobu.com/neoteny/

- “Neoteny”. Bionity.com (ND). https://www.bionity.com/en/encyclopedia/Neoteny.html

- Bogin, Barry. “Neoteny – Biological”. Center for Academic Research & Training in Anthropogeny (ND). https://carta.anthropogeny.org/moca/topics/neoteny-biological

- McNamara, J. K (2012). Heterochrony: the Evolution of Development. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 5, 203-218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-012-0420-3

- Keyte, L. A., Smith, K. K. (2014). Heterochrony and developmental timing mechanisms: changing ontogenies in evolution. Semin Cell Developmental Biology, 0: 99-107. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.06.015

- “Ontogeny and Phylogeny”. Understanding Evolution (ND). https://evolution.berkeley.edu/ontogeny-and-phylogeny/

- Dwyer, Bruce. “Neoteny – why dogs were bred to maintain puppy-like play & features”. Dog Walker of Melbourne (ND). https://www.dogwalkersmelbourne.com.au/articles-dog-walking-pet-sitting/71-dog-neoteny-puppy-love

- Lindo, John. “Why are modern dog breeds so different from one another?” Loyal for Dogs, 12-09-22. https://loyalfordogs.com/posts/why-are-modern-dog-breeds-so-different-from-one-another

- Skulachev, P. V. Holtze, S., Vyssokikh, Y. M., Bakeeva, E. L., Skulachev, V. M., Markov, V. A., Hildebrandt, B. T., Sadovnichii, A. V. (2017). Neoteny, Prolongation of Youth: From Naked Mole Rats to “Naked Apes” (Humans). Physiological Reviews, 97(2): 699-720. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00040.2015

- Orr, E. M., Garbarino, R. V., Salinas, A., Buffenstein, R. (2016). Extended Postnatal Brain Development in the Longest-Lived Rodent: Prolonged Maintenance of Neotenous Traits in the Naked Mole-Rat Brain. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00504

- Groef, D. B., Grommen, H. V. S., Darras, M. V. (2018). Forever young: Endocrinology of paedomorphosis in the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). General and Comparative Endocrinology, 266, 194-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.05.016

- “Axolotls-Biology”. Axolotols.org (ND).

- Tottenham, N. (2020). Early Adversity and the Neotenous Human Brain. Biological Psychiatry, 87(4): 350-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.06.018

- Somel, M., Franz, H., Yan, Z., Khaitovich, P. (2009). Transcriptional neoteny in the human brain. PNAS, 106(14): 5743, 5748. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900544106

- Shi, L., Luo, X., Jiang, J., Chen, Y., Liu, C., Hu, T., Li, M., Lin, Q., Li, Y., Huang, J., Wang, H., Niu, Y., Shi, Y., Styner, M., Wang, J., Lu, Y., Sun, X., Yu, H., Ji, W., Su, B. (2019). Transgenic rhesus monkeys carrying the human MCPH1 gene copies show human-like neoteny of brain development. National Science Review, 6(3): 480-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwz043

- Li, M., Tang, H., Shao, Y., Wang, M., Xu, H., Wang, S., Irwin, M. D., Adeola, C. A., Zeng, T., Chen, L., Li, Y., Wu, D. (2020). Evolution and transition of expression trajectory during human brain development. BMC Ecology and Evolution, 20, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-020-01633-4

- Choi Q., Charles. “Being More Infantile May Have Led to Bigger Brains”. Scientific American, 07-01-09. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/being-more-infantile/

- Schmidt, A. L., Poole, L. K. (2019). On the bifurcation of temperamental shyness: Development, adaptation, and neoteny. New Ideas in Psychology, 53, 13-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.04.003

- Lee, A. L., Karabina, A., Broadwell, J. L., Leinwand, A. L. (2019). The ancient sarcomeric myosins found in specialized muscles. Skeletal Muscle, 9, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13395-019-0192-3

- McCollum, A. M., Sherwood, C. C., Vinyard, J. C., Lovejoy, O. C., Schachat, F. (2006). Of muscle-bound crania and human brain evolution: The story behind the MYH16 headlines. Journal of Human Evolution, 50(2): 232-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.10.003

- Oh, J. H., Choi, D., Goh, J. C., Hahn, Y. (2015). Loss of gene function and evolution of human phenotypes. BMB Reports Online, 48(7): 373-379. 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.7.073

- Perry, H. G., Verrelli, C. B., Stone, C. A. (2005). Comparative Analyses Reveal a Complex History of Molecular Evolution for Human MYH16. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 22(3): 379-382. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msi004

- Perry, H. G., Kistler, L., Kelaita, A. M., Sams, J. A. (2015). Insights into hominin phenotypic and dietary evolution from ancient DNA sequence data. Journal of Human Evolution, 79, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.10.018

- Hunt, K. (2020). Thews, Sinews, and Bone: Chimpanzee Anatomy and Osteology. Chimpanzee: Lessons from our Sister Species. 97-118. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316339916.007

- Groves, P. C. (2017).The latest thinking about the taxonomy of great apes. International Zoo Yearbook, 52(1), 16-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/izy.12173

- Mitteroecker, P., Gunz, P., Bernhard, M., Schaefer, K., Bookstein, L. F. (2004). Comparison of cranial ontogenetic trajectories among great apes and humans. Journal of Human Evolution, 46(6): 679-698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.03.006

- Zollikofer, E. P. C. (2012). Chapter 13 – Evolution of hominin cranial ontogeny. Progress in Brain Research, 195, 273-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00013-1

- Pérez-Claros, A. J., Palmqvist, P. (2022). Heterochronies and allometries in the evolution of the hominid cranium: a morphometric approach using classical anthropometric variables. Paleontology and Evolutionary Science, 10:e13991. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13991

- Scott, A. N., Strauss, A., Hublin, J., Gunz, P., Neubauer, S. (2018). Covariation of the endocranium and splanchnocranium during great ape ontogeny. PLoS ONE, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208999

- Neubauer, S., Gunz, P., Hublin, J. (2009). The pattern of endocranial ontogenetic shape changes in humans. Journal of Anatomy, 215(3): 240-255. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01106.x

- Zollikofer, E. P. C., Bienvenu, T., Beyene, Y., Suwa, T., Asfaw, B., White, D.T., Ponce de León, S. M. (2022). Endocranial ontogeny and evolution in early Homo sapiens: The evidence from Herto, Ethiopia. PNAS, 119(32): e213553119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2123553119

- Zollikofer, E. P. C., Bienvenu, T., Ponce de León, S. M. (2016). Effects of cranial integration on hominid endocranial shape. Journal of Anatomy, 230(1): 85-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12531

- Penin, X., Berge, C., Baylac, M. (2002). Ontogenetic study of the skull in modern humans and the common chimpanzees: Neotenic hypothesis reconsidered with a tridimensional procrustes analysis. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 118(1): 50-62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.10044

- Baxland, Beth. “Humans and Other Great Apes”. The Australian Museum, 08-26-22. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/humans-are-apes-great-apes/

- “Neoteny in Humans”. Mun.Ca (ND). https://www.mun.ca/biology/scarr/Neoteny_in_humans.htm

- “Splanchnocranium”. Bone Broke, 06-25-15. https://bonebroke.org/2015/06/25/splanchnocranium/

- van Dyck, I. L., Morrow, M. E. (2017). Genetic control of postnatal human brain growth. Current Opinion in Neurology. 30(1), 114-124. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000405

- Nalley, K. T., Scott, E. J., Ward, V. C., Alemseged, Z. (2019). Comparative morphology and ontogeny of the thoracolumbar transition in great apes, humans, and fossil hominins. Journal of Human Evolution, 134, 102632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.06.003

- Sanders, R. “160,000-year-old fossilized skulls uncovered in Ethiopia are oldest anatomically modern humans.” UC Berkeley News, 06-11-03.

- Morimoto, N., Nakatsukasa, M., Ponce de León, S. M., Zollikofer, E. P. C. (2018). Femoral ontogeny in humans and great apes and its implications for their last common ancestor. Scientific Reports, 8, 1930. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20410-4