Ancient DNA and how we can learn so much from so little

Written by Emily Masterson

Ancient DNA is becoming a powerful tool in the story of human evolution. Never before have we been able to gather so much information from seemingly so little evidence. This microscopic part of an organism holds so much within its tiny coils, and now that we are able to unravel and examine it, our perception of ancient hominins can only grow and expand in new and unexpected ways.

Collecting ancient DNA is currently limited to samples only a few hundred thousand years old. While this does allow scientists to take a closer look at our more recent ancestors and relatives, the chance to explore the genetic makeup of our more ancient ancestors may be lost forever. A combination of contextual clues, radiocarbon dating and DNA analysis work together to build the whole picture of what one small bone fragment can tell us.

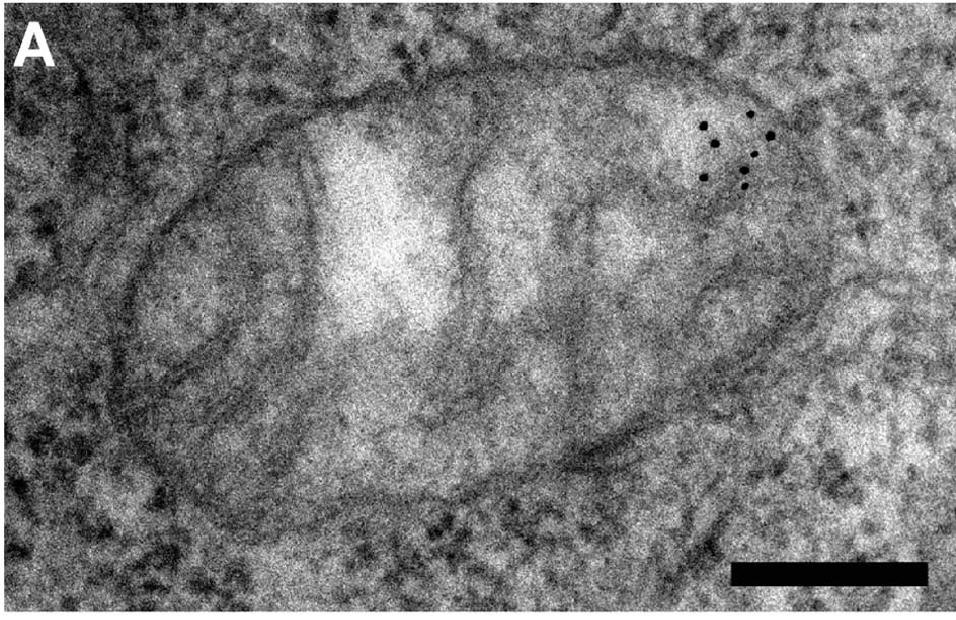

DNA is extracted from samples and then replicated using a technique called PCR so scientists have as much to work with as possible. Due to the degradation of ancient DNA, the sections recovered are often much shorter than scientists would be able to extract from a living specimen. However, DNA from the mitochondria (mtDNA) degrades at half the speed of nuclear DNA. There are also around 1000 mitochondria in each cell, and 2-10 copies of the mtDNA in each of these. The odds of there being mtDNA available and of high enough quality for study is much higher than DNA found in the nucleus of cells.

This technique of using mtDNA has been used in several cases of Denisovan and Neanderthal explorations. We have been able to tell a huge part of the Denisovan story, with only a few very tiny samples thanks to this DNA. But just the isolated DNA can’t tell us much, it requires a library of genetic samples, which only start to tell a story once we compare them.

The human genome has been mapped and scientists have a pretty good idea of what codes for what, and can see shared trends across populations. By comparing the DNA of ancient hominins to human genomes, we can start to reveal surprising data.

When neanderthal DNA was analysed and compared to the human genome, we learnt that our last common ancestor with them was 800,000 years ago, but because of the way mitochondrial DNA is inherited, we actually share a common mitochondrial ancestor only 500,000 years ago. While nuclear DNA is shared and combined during reproduction, allowing for more gene flow and changes to a population, mitochondrial DNA is passed down, unchanged, though the matrilineal line.

Between the information of human genomes and that which we have learnt from neanderthals, it places scientists in an excellent position to understand the DNA of new hominin samples when they become available.

In the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia, a site was excavated and a single important phalanx, or finger bone, was discovered in layer 11. The phalanx was too small to radiocarbon date, so using other samples found in the layer, such as a rib with regular incisions (indicating that it was associated with human occupation) the layer was determined to be more than 50,000 years old.

The entire internal structure of the phalanx was used to gather DNA, and this single bone proved to be an exceptional sample. Whereas previous neanderthal studies have only been able to retrieve up to 5% of endogenous neanderthal DNA and 95% microbial DNA, this phalanx provided a massive 70% endogenous DNA. Not only this, but neanderthal studies had retrieved DNA which was 50 base pairs long, and this phalanx, even after processing and treatment, managed to extract samples with 58 base pairs. This meant that the samples were incredibly well preserved and scientists had a lot more to work with. It’s not known why this was preserved so well in a temperate environment, but it is similar to what is expected from samples retrieved from permafrost.

Once the DNA had been extracted and read, the real fun began. When compared to human and previously studied neanderthal mtDNA, it was determined that this was a new species which split from present day Africans 804,000 years ago and Vindija neanderthals 640,000 years ago. From just one bone, we were able to place this new species on the map of human evolution, and determine that it split from neanderthals after they branched off from the human line. We can then examine in a lot of detail, where exactly their DNA shows up in modern populations and learn how they might have spread across the globe.

It seems that there is very little evidence that Denisovans made their way into the genes of the Eurasian population, but much stronger evidence that they are present in modern Melanesian populations. It is estimated that these populations share 4.86% of their DNA (plus or minus 0.5%) with Denisovans compared to 0% in African populations. Whereas Neanderthal DNA can be seen across all non-African populations, this gives us a good understanding of where Denisovans may have ranged.

Already, so much had been learnt from such a small sample. But more was to come when in layer 11.1 of the same cave, a single molar was discovered. It is most likely an upper third molar (but the possibility exists that it could be a second molar), and almost completely intact. If it is a third molar, then from morphology alone we can see that it is an unusual size for the Homo genus (except for H. habilis and H. rudolfensis) and more like the third molar of Australopithecines.

15,094 mtDNA sequences were extracted from 50mg of dentin from the root of this molar, and while 380 are different from that of humans and neanderthals, only 2 differ from the mtDNA collected from the phalanx. This proved that these two fossils found in the cave were from the same population, but from two different individuals. The time since the last common ancestor for these two individuals is estimated to be around 7,500 years.

The mtDNA from the molar supported the previous conclusion that denisovans are distinct from neanderthals and modern humans, something which may have been more tricky to prove on morphology alone. But the morphology combined with the DNA can help us work out the solutions to more questions about this population. Questions such as “Why is the molar so primitive if they share lineage with humans and neanderthals?” One answer is that these features were retained in denisovans while they were lost in modern humans and neanderthals, or that there was a reversal to ancestral traits after the split.

One interesting answer is that these archaic traits arrived through gene flow from another hominin which has not been DNA sequenced yet. If this hominin’s genome is ever found, it could expand our knowledge of Denisovans so much.

One last bone fragment was discovered and analysed from this cave recently, but this time it was much older. The layer was dated to 200,000 years ago, but with DNA analysis, we also know that this individual was a male who had inherited 5% of his genome from a population of neanderthals we had not yet sequenced. He also came from a different population of denisovans than the others found previously. Lastly, and perhaps most interestingly, the DNA found in the phalanx contained unknown portions, DNA not found in the samples from humans or neanderthals, which hinted at an unknown (or un-analysed) hominin, and this DNA was also present in the older male individual. Thanks to DNA, as we expand the libraries, we can begin to construct more detailed timelines of who might have lived in the caves, and what their relationship to other hominins might have been.

We can learn so much from DNA analysis, and the libraries are only expanding with more information to help our understanding grow. As we have seen, it could only take one tiny bone fragment to completely change the course of history!

Chen, F.; Welker, F.; Shen, C.-C.; et al. (2019). “A late Middle Pleistocene Denisovan mandible from the Tibetan Plateau” (PDF). Nature. 569 (7756): 409–412. Bibcode:2019Natur.569..409C.

Gibbons, Anne (2019). “First fossil jaw of Denisovans finally puts a face on elusive human relatives”. Science. doi:10.1126/science.aax8845. S2CID 188493848.

Iborra, F.J., Kimura, H. & Cook, P.R. (2004) The functional organization of mitochondrial genomes in human cells . BMC Biol 2, 9 . https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-2-9

Krause J, Fu Q, Good JM, Viola B, Shunkov MV, Derevianko AP, Pääbo S. (2010) The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia. Nature. Apr 8;464(7290):894-7.

Merheb M, Matar R, Hodeify R, Siddiqui SS, Vazhappilly CG, Marton J, Azharuddin S, Al Zouabi H. (2019) Mitochondrial DNA, a Powerful Tool to Decipher Ancient Human Civilization from Domestication to Music, and to Uncover Historical Murder Cases. Cells. May 9;8(5):433.

Meyer, M.; Kircher, M.; Gansauge, M.-T.; et al. (2012). “A High-Coverage Genome Sequence from an Archaic Denisovan Individual”. Science. 338 (6104): 222–226.

Reich, D.; Green, R. E.; Kircher, M.; et al. (2010). “Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia” (PDF). Nature. 468 (7327): 1053–60.

Slon V, Viola B, Renaud G, Gansauge MT, Benazzi S, Sawyer S, Hublin JJ, Shunkov MV, Derevianko AP, Kelso J, Prüfer K, Meyer M, Pääbo S. (2017) A fourth Denisovan individual. Sci Adv. Jul 7;3(7):e1700186.

One thought on “How Ancient DNA can be a powerful tool”