When We Became Human

Introduction: A Question as Old as Us

What does it truly mean to be human? Is humanity defined by our anatomy, by our actions, or by the way we think? When did we cross that invisible line from being just another species to becoming uniquely human? Paleoanthropologists—researchers who study the evolution of humans—continue to debate this fascinating question. In truth, our humanity may not be marked by a single event, but rather a gradual accumulation of changes in physical form, behavior, and cognitive capabilities—an evolutionary mosaic, not a singular turning point.

The Physical Foundations: Standing Tall, Reaching Far

Physically, one of the earliest hallmarks of humanity is bipedalism—the ability to walk upright on two legs. Fossils such as those of Australopithecus afarensis, including the famous Lucy, dating to around 3.2 million years ago, provide compelling evidence of early upright locomotion (Johanson et al., 1978). This adaptation did more than simply allow our ancestors to stand tall. It freed our hands for other tasks like carrying food, using tools, and eventually making gestures—all of which opened new cognitive and social opportunities. Standing on two legs helped shape our skeletons, our movement, and even the ways we interact with each other.

Another physical marker is the evolution of the genus Homo, beginning with Homo habilis around 2.4 million years ago. Homo habilis, or “handy man,” earned its nickname from its skill in crafting stone tools. However, even earlier than Homo habilis, we find the Lomekwian tool industry, discovered in Kenya and dating back to around 3.3 million years ago, associated not with Homo but possibly with Australopithecus or Kenyanthropus (Harmand et al., 2015). These primitive tools challenge the idea that tool use was exclusive to our genus and suggest that technological innovation predates Homo. Toolmaking not only required physical dexterity but also marked a behavioral shift toward greater reliance on technology, cooperation, and even planning—early hints at the symbolic thinking that would later define us.

Fire and Food: Cooking Up Intelligence

Cooking food, another significant milestone, likely emerged around 1 million years ago with Homo erectus. Cooking fundamentally altered human anatomy and lifestyle by making food easier to digest, enabling smaller gut sizes, and facilitating larger brain growth (Wrangham, 2009). This transformation helped redirect energy from digestion to brain development, allowing our cognitive capacities to flourish. Beyond the biology, the act of cooking likely fostered social bonds—gathering around the fire, sharing meals, and protecting communal hearths may have strengthened group cohesion and communication.

Symbols and Thought: The Cognitive Bloom

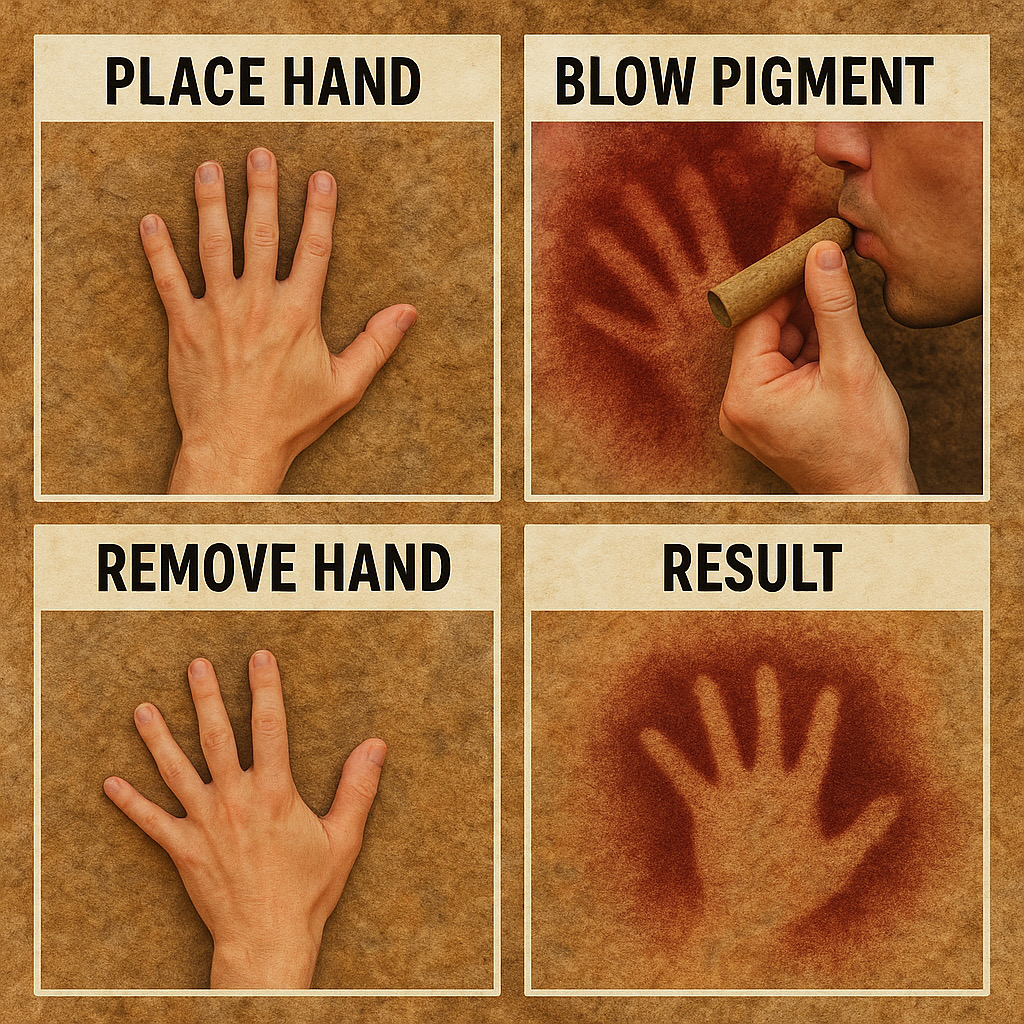

Yet, behavior alone isn’t the complete story. Cognitive evolution is equally crucial. Around 300,000 years ago, with the rise of Homo sapiens, cognitive abilities began to flourish, evidenced by sophisticated tools, controlled use of fire, and eventually, symbolic expressions such as art. The appearance of art—especially cave paintings like those in Chauvet Cave (around 32,000 years old) and Altamira Cave (over 20,000 years old)—symbolizes a new depth of human cognition: imagination, abstraction, and cultural expression (Clottes & Lewis-Williams, 1998). These are not just pictures on a wall. They are messages from minds like ours, encoding stories, rituals, and perhaps even emotions across vast stretches of time.

We also see this in personal adornment—beads, ochre, carved bones—material signals of identity and belonging. Language, though harder to fossilize, likely evolved hand-in-hand with these symbolic practices. The ability to share ideas, gossip, warn, teach, and plan is arguably the most powerful tool ever invented. Some researchers even argue that the evolution of language and storytelling is what bound early humans into cohesive groups, setting the stage for cultural explosion.

The Human Spectrum: Not Just Us

However, what makes us human may extend beyond these individual milestones. Recent research highlights complex social structures, emotional connections, and even moral frameworks in Neanderthals and other hominins, challenging a strictly human-centric view of cognitive and cultural capacities (Zilhão et al., 2010). Neanderthals buried their dead, cared for the injured, created art, and may have had spiritual beliefs. The boundary between “us” and “them” grows fuzzier with every discovery.

The Ongoing Journey: A Web, Not a Line

Today, paleoanthropologists increasingly view the journey to humanity not as a single threshold event but as a complex web of physical, behavioral, and cognitive developments woven through millions of years. Each adaptation—whether it was making a hand axe, taming fire, or forming long-term social bonds—served as a stitch in the greater fabric of our shared evolutionary path. We are just beginning to understand the intricate connections between these threads, many of which still lie buried beneath layers of earth and time.

Looking Ahead: Writing the Next Chapter

Future research will further unravel this tapestry. Advances in technology, from high-resolution imaging to ancient DNA sequencing, are unlocking secrets that were once thought lost to time. Interdisciplinary studies—linking archaeology, genetics, psychology, and even artificial intelligence—promise exciting insights into our shared past. As our tools for studying human origins grow more sophisticated, so too does our appreciation for the complexity and diversity of our ancestors. Every fossil, every scrap of ochre, every strand of DNA tells part of the epic story of us.

By exploring how we became human, we gain deeper insights into ourselves. We recognize that our humanity is not just something we inherited, but something we build every day—through acts of kindness, creativity, curiosity, and resilience. Our story isn’t finished. In fact, it’s still being written. And the more we learn about where we came from, the better equipped we are to decide where we’re going.

Ultimately, our humanity is not defined solely by our ability to walk upright, craft tools, cook food, or create art. Rather, it is the cumulative story of innovation, survival, adaptation, and imagination—a story still being written with each new discovery. To be human is to be in process, always becoming, always reaching—not just into the past, but forward into the future.

References

- Clottes, J., & Lewis-Williams, D. (1998). The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance and Magic in the Painted Caves. Harry N. Abrams.

- Harmand, S., Lewis, J. E., Feibel, C. S., Lepre, C. J., Prat, S., Lenoble, A., … & Roche, H. (2015). 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature, 521(7552), 310–315.

- Johanson, D. C., Taieb, M., & Coppens, Y. (1978). Pliocene hominids from the Hadar Formation, Ethiopia (1973–1977): Stratigraphic, chronological, and paleoenvironments contexts, with notes on hominid morphology and systematics. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 49(3), 373–402.

- Wrangham, R. (2009). Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. Basic Books.

- Zilhão, J., Angelucci, D. E., Badal-García, E., d’Errico, F., Daniel, F., Dayet, L., … & Villaverde, V. (2010). Symbolic use of marine shells and mineral pigments by Iberian Neanderthals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(3), 1023–1028.

Hi Seth,

You raise an interesting question. “Human” is not a formal scientific term, and so, like “dog” or “cat” one can move the goalposts to improve the score. A rabbit-sized “service dog/comfort animal” is a dog, but so, too is Labrador retriever, and, arguably a timber wolf. Cute “Mr. Snuffles.” the house-bound cat? Yup, a cat. The Bengal tiger that just ate another idiot tourist? A cat. A big cat, but a cat.

In my teaching and writing, I reserve the term, human, for Homo sapiens. We were the only hominins around when the term, human, came into usage in English during the later Middle Ages. The other guys, hominins or whatever non-Linnaean term in use for them, like Neandertals, Denisovans, Hobbits, etc.

Your essay uses a “checklist” approach to identifying humans. This is similar to various approaches to defining “modern human behavior” or “behavioral modernity.” Chris Henshilwood and Curtis Marean wrote a really good critique of this approach a back in the 1990s (in Current Anthropology).

Keep up the writing. You have a real talent for this.

LikeLike

I love this! Thanks so much for reading and participating! I will look into this work; this was absolutely a more general post to get the gears turning in peoples heads, and it seems to have worked!

LikeLike