Cave Lions being HUNTED by Neanderthals? What?!

Cambridge Journal of Human Behaviour: Call for Undergraduate Submissions

Hello!

On behalf of the Cambridge Journal of Human Behaviour, I have an awesome opportunity to tell you all about!

They are currently accepting undergraduate work for submissions to their peer reviewed journal! This is a chance to get your work published before you even get to graduate school!

Take look at the call for papers:

I hope you are doing well.

If you could please distribute the following message and attached document to members of your department (especially undergraduates), that would be greatly appreciated.

___________________

Cambridge Journal of Human Behaviour: Call for Submissions (Vol. 2, Issue 3)

The Cambridge Journal of Human Behaviour (CJHB) is now calling for submissions! CJHB is an internationally registered, peer-reviewed journal that is interdisciplinary in nature and dedicated to publishing the exceptional work of undergraduates from across the globe.

We are a diamond open access journal, do not charge fees of any sort (subscription, processing, membership, or otherwise), and permit the author to re-publish their work elsewhere.

The deadline for the third issue of Volume 2 is the 2nd of January, 2024. Submissions are always open and can be submitted online via our website: www.cjhumanbehaviour.com

Specific details for submission:

- Dissertations, projects, and extended essays welcome

- 5,000 words maximum

- Any topic relating to human behaviour (archaeology, anthropology, psychology, biology, etc.)

- Interdisciplinary manuscripts strongly encouraged

- All work must have been completed during the course of a student’s undergraduate studies

- We are now also accepting book reviews

- Word limit: 1,500

- Reviews for books published in 2022 or later welcome

- Revisiting seminal books in a field also permitted

More details can be found on our website! For reference, check out our past issues here: https://cjhumanbehaviour.com/publications/.

___________________

Any questions or concerns can be directed to myself Seth, at journalhumanbehaviour@cambridgesu.co.uk

Pretty cool huh!

I hope to hear from you, and see your submissions soon!

When did Homo erectus first leave Africa?-Guest post by Mekhi

Introduction

It is commonly thought that Homo erectus was the first human species to leave our home continent of Africa. Though there is some evidence of earlier migrations accomplished by other species, it is clear that Homo erectus was the first species to accomplish mass migrations throughout Eurasia. Homo erectus fossils have been uncovered from right outside of Africa in sites in the Middle East, and extending all the way into Asia, going into Indonesia and even as far as China.

This begs a variety of questions, mainly, why did Homo erectus leave Africa, and when did these migrations begin? There are some early sites right outside of Africa that give a good idea of generally when this species first began migrating. The closest site outside of Africa that contains Homo erectus remains is ‘Ubeidiya, Jordan. This site contains great faunal and lithic assemblages, and most importantly, Homo erectus remains, including a left parietal bone, a lumbar vertebrae, and some dental remains.

Research on this site shows that during the Pleistocene, when Homo erectus was living there, this area resembled a steppe environment, with very large water bodies and woodlands, very different from the environments in Africa. It appears that Homo erectus began migrating due to environmental changes. This answers the question of why they left, but not necessarily when. Homo erectus at ‘Ubeidiya are about 1.5 million years old, but there is an even older site farther from Africa that is even older.

Out of Africa

Even as predicted by Charles Darwin, humans and our evolutionary lineage originated in Africa. This was originally thought by the fact that our two closest extant relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas, also live in Africa, but it is now backed up by more fossil and genetic evidence. The migrations of humans out of Africa is creatively referred to as “Out of Africa”. Throughout the history of our evolution, there have been many migrations, all of which seem to have been accomplished by multiple different species.

‘Out of Africa 1’ refers to the migrations of Homo erectus throughout Eurasia, in which they migrated throughout Eurasia, especially in Asia, beginning roughly 2 million years ago. These migrations are often thought to be the first times humans left Africa, but there is potential evidence of earlier migrations done by a different species.

Oldowan style stone tools have been found in Zarqa Valley, Jordan, just outside of geopolitical Africa, dating to 2.4 million years ago. This suggests an earlier migration of an earlier hominin, something similar to Homo habilis, soon after the evolution of the Homo genus. Other Oldowan style tools have also been found in China, dating to 2.1 million years ago.

All of these tool sites date to before Homo erectus ever left Africa and are more primitive than Homo erectus, suggesting that earlier migrations of early Homo took place 2.4 million years ago. These migrations could explain the origins of other primitive hominin species outside of Africa, such as Homo floresiensis in the island of Flores, in Indonesia.

The first mass migrations were accomplished later, by Homo erectus, first migrating into the middle east, in sites like ‘Ubeidiya at 1.5 million years ago, and in an even older site, known as Dmanisi, which contains the oldest fossil remains of Homo erectus outside, at 1.8 million years old. This site contains great information about the earliest migrations of Homo erectus, and has been heavily studied. With the new research done, we now have a great understanding of the humans that lived there and what their lives were like.

The Life and Ecology of Dmanisi

The Dmanisi site is a fossil cave site which was previously laid beneath a medieval city. Dmanisi has held lots of Pleistocene faunal remains that have been uncovered, including about 40 fossil hominin remains. These fossils, along with the modern life of this area, gives a good idea of what the world was like there about 2 million years ago.

Many amphibian, reptile, and mammal remains have been found. Amphibian and reptile species which have been found here include the European green toad (Bufo viridis), Greek tortoises (Testudo graeca), the European green lizard (Lacerta viridis), and several species of snake in the genera Elaphe and Natrix. Because all of these species are extant and still around today at Dmanisi, they can still be studied, allowing for a greater understanding of the ecology, landscape, and climate of this area.

By using the Mutual Climatic Range method (studying modern life to compare to prehistoric life), it has been shown that the climate at Dmanisi was warm and dry, similar to that of modern Mediterranean climates, though the average temperature was slightly warmer than it is today. The average rain levels were also slightly lower than it is today, except for in the winter.

The paleofauna of Dmanisi also indicates that the landscape was arid, with semi deserts, Mediterranean forests, and rocky substrate with bushy areas. Research of small mammals from this site, such as shrews, hamsters, and pikas, shows that roughly 36.5% of this environment was open-dry habitat, 25.7% water edge, 21% rocky, 15.5% open-wet habitat, and 1.3% woodland.

These mammals, along with other carnivoran mammals found at this site, would have provided a good meat source for the hominins living there, aiding in the transition to a more carnivorous diet in hominins. As hominin populations migrated into this area, they slowly adapted to the unique environment, which could explain the unique morphology they possessed.

The Dmanisi Hominins

The fossil hominins from Dmanisi are the oldest, unquestionable, confirmed hominins outside of Africa. By using 40Ar/39Ar (Argon-Argon) dating, paleomagnetism, and paleontologic constraints, it has been determined that these hominins lived around 1.8-1.7 million years ago. Morphologically, they are very basal, resembling early Homo in many ways, but also resembling the later Asian Homo erectus.

They are currently placed in the species Homo erectus, but have been sometimes placed in a separate species, Homo georgicus, though this species name is not commonly accepted at this time. There is lots of variation between the different individuals at the site, especially in their mandibles, but they are similar enough in overall morphology and time to belong to the same population. Their jaws and crania seem to be dimorphic in size, which could represent possible sexual dimorphism in the population.

The hindlimb anatomy of these hominins was similar to that of modern humans, and would have been useful for hunting down prey by using persistence hunting. Dental microwear analysis of the teeth of these hominins shows that their diets were consistent with other migrating populations of Homo erectus. Their teeth also share several synapomorphies (evolutionary traits shared between two related lineages) with Australopithecus and early Homo, especially in size.

The Dmanisi hominins would have used the rocky terrain they lived in to produce many Oldowan style stone tools, mainly using basalt and andesite as their two main blanks for these tools. Many cores, flakes, and rock debris have been found, showing that all stages of stone flaking were present. The stone knapping wasn’t very elaborate however, as most of the stones were unifacial rather than the intricate bifacial tools produced by later Homo erectus.

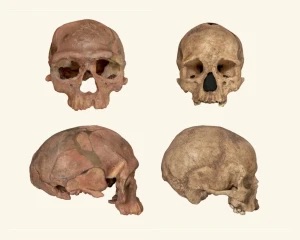

The Dmanisi Specimens

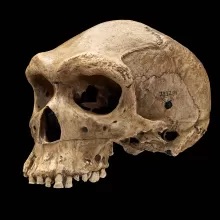

There are 5 cranial specimens from Dmanisi, and several associated mandibular specimens, along with many other post cranial elements. The first specimen is known as D2280.

D2280

This specimen is the first of 5 cranial specimens, and is also the largest. The specimen is only a skull cap, but still has lots of well preserved features. From these features, we can tell that this individual is a male. Significant traits found in this specimen include a large supraorbital torus (brow ridge), a strong angular torus at the back of the skull, and a cranial capacity of about 775 cc.

D2282

This specimen is the second cranial specimen from Dmanisi, belonging to a young female. It is similarly incomplete to D2280, with the majority of the interorbital region (consisting of the eyes and nose) incomplete. The zygomatic and maxillary bones are complete however. The mastoid portions at the lower back of the skull are partially crushed but are still preserved. The mandibular specimen D211 is associated with the cranium. This specimen possessed a cranial capacity of about 650 cc.

D2700

The third cranial specimen, D2700, belonged to a subadult male with partially erupted back molars. This specimen has damage to the maxilla and zygomatic bones, and is missing some teeth, though other scattered teeth found in the site fit in the sockets well. The D2735 mandible is associated with this specimen. This specimen had a cranial capacity of about 600 cc.

D3444

D3444 is the fourth, and perhaps the most important specimen out of the five, and has great implications for the sociality of the Dmanisi hominins. This specimen belonged to an elderly male who had naturally lost all of his teeth. In the associated D390 mandible, the canine teeth sockets hadn’t healed over, suggesting he kept those teeth. However the teeth sockets in the cranium had fully healed over, showing that he had survived for a good while after he lost them. There are a few ideas of how he could have survived this. He could have eaten plants, softer meat such as brain matter or bone marrow, but must have been in some way cared for by the other individuals, showing evidence of compassion and care early on in the species. This specimen had a cranial capacity of about 650 cc.

D4500

D4500 is the last cranial specimen, and seems to be the most unique and complete out of the five, belonging to an adult male. This specimen has a very large face, with squared maxilla similar to Homo habilis, but a very small brain and a face similar to Australopithecus. Its cranial capacity was about 546 cc. This specimen had very bar-like browridges, and very large teeth which appear to be worn down and infected. The D2600 mandible is associated with this specimen.

Conclusion

There is little question that humans evolved in Africa and later migrated out of it in several waves. Homo erectus is typically considered the first species to have done this, in an event referred to as ‘Out of Africa 1’, in which it traveled throughout Europe and Asia. Earlier migrations may have taken place, but none as drastic, widespread, and long lasting as what Homo erectus did.

The earliest Homo erectus remains outside of Africa have been found in two main sites. The closest site to Africa is ‘Ubeidiya, at 1.5 million years ago, and even older but farther away, at Dmanisi.

The Dmanisi hominins are very important for our understanding of our evolution. Not only do they show when humans migrated out of Africa, when we shifted to more carnivorous diets, but they show when we began caring for each other, which was very important for our sociality, compassion, and morality.

Sources

- Schmid, P. (2015). Nadaouiyeh – A Homo erectus in Acheulean context. L’Anthropologie, 119(5), 694-705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anthro.2015.10.011

- Belmaker, M., Tchernov, E., Condemi, S., Bar-Yosef, O. (2002). New evidence for hominid presence in the Lower Pleistocene of the Southern Levant. Journal of Human Evolution, 43(1), 43-56. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.2002.0556

- Glausiusz, Josie. “What Drove Homo Erectus Out of Africa?” Smithsonian Magazine, 10-19-21. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-drove-homo-erectus-out-of-africa-180978881/

- López, S., van Dorp, L., Hellenthal, G. (2015). Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate. Evolutionary Bioinformatics, 11(Suppl 2): 57-68. 10.4137/EBO.S33489

- Baxland, Beth, Dorey, Fran. “The first migrations out of Africa”. The Australian Museum, 04-03-20. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/the-first-migrations-out-of-africa/

- Dorey, Fran. “When and where did our species originate?” The Australian Museum, 20-01-20. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/when-and-where-did-our-species-originate/

- Johnson, Stephen. “Out of Africa: Not just once, but many times”. Big Think, 02-04-22. https://bigthink.com/the-past/out-of-africa-events/

- Dorey, Fran. “Homo erectus”. The Australian Museum, 16-10-20. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-erectus/

- Van Arsdale, A. P. (2013) Homo erectus – A bigger, Smarter, Faster Hominin Lineage. Nature Education Knowledge 4(1):2. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/homo-erectus-a-bigger-smarter-97879043/

- Baxland, Beth, Dorey, Fran. “Homo ergaster”. The Australian Museum, 28-01-22. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-ergaster/

- Scardia, G., Parenti, F., Miggins, P. D., Gerdes, A., Araujo, M. J. A., Neves, A. W. (2019). Chronologic constraints on hominin dispersal outside Africa since 2.48 Ma from the Zarqa Valley, Jordan. Quaternary Science Reviews, 219, 1-19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.06.007

- Argue, D., Moorwood, J. M., Sutikna, T., Jatmiko, Saptomo, W. E. (2009). Homo floresiensis: a cladistic analysis. Journal of Human Evolution, 57(5), 623-639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.05.002

- Akhilesh, K., Pappu, S. (2015). Bits and pieces: Lithic waste products as indicators of Acheulean behaviour at Attirampakkam, India. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 4, 226-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.08.045

- Dennell, W. R., Louys, J., O’Regan, J. H., Wilkinson, M. D. (2013). The origins and persistence of Homo floresiensis on Flores: biogeographical and ecological perspectives. Quaternary Science Reviews, 95, 98-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.06.031

- Li, H., Kuman, K., Li, C. (2018). What is currently (un)known about the Chinese Acheulean, with implications for hypotheses on the earlier dispersal of hominids. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 17, (1-2), 120-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2015.09.008

- Agustí, J., Lordkipanidze, D. (2010). How “African” was the early human dispersal out of Africa? Quaternary Science Reviews, 30, (11-12), 1338-1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.012

- Parés, M. J., Duval, M., Arnold, J. L. (2011). New views on an old move: Hominin migration into Eurasia. Quaternary International, 295, 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2011.12.015

- Blain, H., Agusti, G., Lordkipanidze, D., Rook, L., Delfino, M. (2014). Paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental context of Early Pleistocene hominins from Dmanisi (Georgia, Lesser Caucasus) inferred from the herpetofauna assemblage. Quaternary Science Review, 105, 136-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.10.004

- Agusti, J., Chochishvili, G., Lozano-Fernández, I., Furió, M., Piñero, P., Marfà d. R. (2022). Small mammals (Insectivora, Rodentia, Lagomorphia) from the Early Pleistocene hominin-bearing site of Dmanisi (Georgia). Journal of Human Evolution, 170, 103228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103238

- Tappen, M., Bukhsianidze, M., Ferring, R., Coil, R., Lordkipanidze, D. (2022). Life and death at Dmanisi, Georgia: Taphonomic signals from the fossil mammals. Journal of Human Evolution, 171, 103249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103249

- Messager, E., Lebreton, V., Marquer, L., Russo-Ermolli, E., Orain, R., Renault-Miskovsky, J., Lordkipanidze, D., Despriée, J., Peretto, C., Arzarello, M. (2010). Paleoenvironmental of early hominins in temperate and Mediterranean Eurasia: new paleobotanical data from Paleolithic key-sites synchronous natural sequences. Quaternary Science Reviews, 30, (11-12), 1439-1447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.09.008

- Mgeledze, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Moncel, M., Despriee, Chagelishvili, R., Nioradze, M., Nioradze, G. (2011). Hominin occupations at the Dmanisi site, Georgia, Southern Caucasus: Raw materials and technical behaviours of Europe’s first hominins. Journal of Human Evolution, 60(5), 571-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.10.00

- Ferring, R., Oms, O., Agustí, J., Lordkipanidze, D. (2011). Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma. PNAS, 108(26), 10432-10436. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1106638108

- Rightmire, P. G., Lordkipanidze, D., Vekua, A. (2005). Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia. Journal of Human Evolution, 50,(2), 115-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.07.009

- Perkins, S. (2013). Skull suggests three early human species were one. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2013.13972

- Gibbons, Anne. “Meet the frail small- brained people who first trekked out of Africa”. Science, 10-22-16, https://www.science.org/content/article/meet-frail-small-brained-people-who-first-trekked-out-africa

- Pontzer, H., Rolian, C., Rightmire, P. G., Jashashvili, T., Ponce de Léon, S. M., Lordkipanidze, D., Zollikofer, E. P. C. (2010). Locomotor anatomy and biomechanics of the Dmanisi hominins. Journal of Human Evolution, 58,(6), 492-504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.03.006

- Skinner, M. M., Gordon, D. A., Collard, J. N. (2006). Mandibular size and shape variation in the hominins at Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia. Journal of Human Evolution, 51,(1), 36-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.01.006

- Rightmire, P. G., Margvelashvili, A., Lordkipanidze, D. (2018). Variation among the Dmanisi hominins: Multiple taxa or one species? American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 168(3): 481-495. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23759

- Pontzer, H., Scott, R. J., Lordkipanidze, D., Ungar, S. P. (2011). Dental microwear texture analysis and diet in the Dmanisi hominins. Journal of Human Evolution, 61,(6), 683-687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.08.006

- Martinón-Torres, M., Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Gómez-Robles, A., Margvelashvili, A., Prado, L., Lordkipanidze, D., Vekua, A. (2008). Dental remains from Dmanisi (Republic of Georgia): Morphological analysis and comparative study. Journal of Human Evolution, 55, (2), 249-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.12.008

- Tsvarianti, David. “Hominins”. Dmanisi, ND. https://www.dmanisi.ge/page?id=12&lang=en

- “D2282”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/d2282

- “D3444”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/d3444

- Lordkipanidze, D., Vekua, A., Ferring, R., Rightmire, P. G., Zollikofer, E. P. C., Ponce de Léon, S. M., Agusti, J., Kiladze, G., Mouskhelishvili, A., Nioradze, G. (2006). A fourth hominin skull from Dmanisi, Georgia. The Anatomical Record, 288A,(11), 1146-1157. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.a.20379

- Rightmire, P. G., Ponce de Léon, S. M., Lordkipanidze, D., Margvelashvili, A., Zollikofer, E. P. C. (2017). Skull 5 from Dmanisi: Descriptive anatomy, comparative studies, and evolutionary significance. Journal of Human Evolution, 104, 50-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.01.005

- Schwartz, H. J., Tattersall, I., Chi, Z. (2014). Comment on “A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Biology of Early Homo”. Science, 344,(6182), 360. DOI: 10.1126/science.1250056

- Craze, P. (2013). Early human evolution and the skulls of Dmanisi. Significance, 10,(6), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2013.00703.x

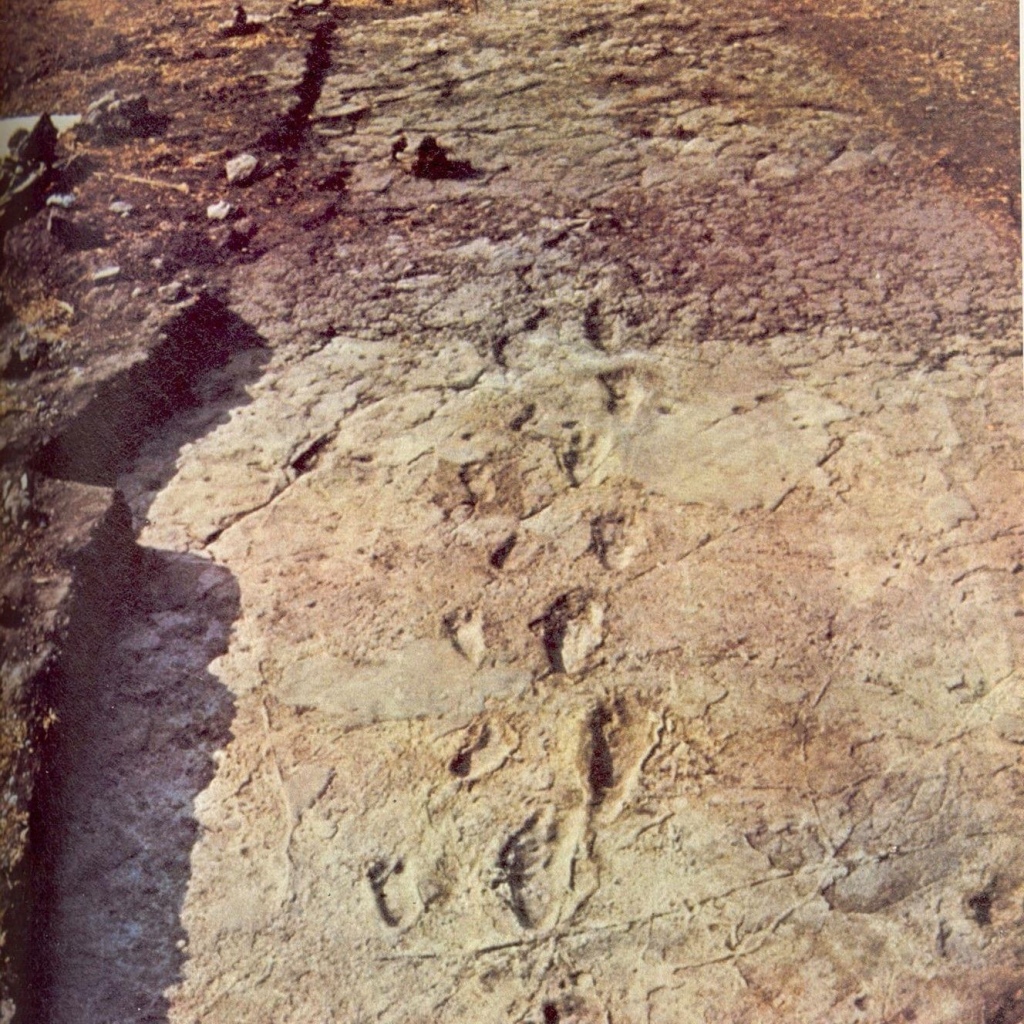

The Laetoli Footprints September 15th , 1976

Not far from Olduvai George, a famous #fossil locality that was frequented by the Leakeys and colleagues, and a very important place where many lithic (stone) tools have been found, at first believed to be from Homo habilis, the first of our genus, but now is thought to be pushed back much farther in time to the Australopithecines.

Well, not far from here, on another excavation, Mary Leakey, wife of Louis Leakey, and discoverer of Zinj and many other important finds, hit the jackpot once again!

Amazingly, she came across a 75-ft trail of hominin footprints!!! It was unlike anything ever seen before!

So what does this mean? Well, as you can tell that is a two-legged, upright walking animal. This means they were #bipedal, which only has occurred habitually in those of our clade, the Hominid family. This was proof, that our ancestors were walking upright at least 3.7 mya. This was the proof that so many had been looking for!

Many more footprints of hominins from Africa and Eurasia have been found since, but there was something special about these, and they’re still is today.

After later excavation by the #Leakeys and Dr. Tim White, it was concluded that the footprints must belong to #Australopithecus #Afarensis, or the species “Lucy” belongs to. Discovered in 1976, this would change our view of humanity forever.

Look at that!

What do you think about this?

Do a little research on the topic and lets start a discussion! What do you think the #ignificance of this find is to our understanding of #Human #Origins?

Anatomy and Paleoanthropology, a chat with Dr. Bernard Wood

Premiering at Noon!

I am so excited to welcome you all to the next episode of #TheStoryofUs! On this episode, I am honored to talk to prestigious professor Dr. Bernard Wood of George Washington University. We discuss his career, starting as a surgeon and medical doctor and then finding his way into our deep human past and never looking back. Taking a unique look at our origins from an anatomical point of view, Dr. Wood has been a cornerstone of much of what we understand about hominin anatomy and evolutionary morphology.

“Bernard Wood is The University Professor of Human Origins and Professor of Human Evolutionary Anatomy at George Washington University. Dr. Wood is a medically qualified paleoanthropologist who practiced as a surgeon before moving into full-time academic life in 1972. In 1982, he was appointed to the S.A. Courtauld Chair of Anatomy in The University of London, and in 1985 he moved to The University of Liverpool to the Derby Chair of Anatomy and to the Chairmanship of the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology. He was appointed the Dean of The University of Liverpool Medical School in 1995 and served as Dean until his move to Washington in the fall of 1997. When he was still a medical student, he joined Richard Leakey’s first expedition to what was then Lake Rudolf in 1968 and he has remained associated with that research group, and pursued research in paleoanthropology, ever since. His research centers on increasing our understanding of human evolutionary history by developing and improving the ways we analyze the hominin fossil record, and on using the principles of bioinformatics to improve the ways we store and collate data about the hominin fossil record. He has a special interest in the recognition of species and genera in the hominin fossil record, and he collaborates with researchers interested in the evolution of non-hominins in the interests of ensuring that we analyze hominin evolution in a proper comparative context. He has written one of the monographs in the series on the Koobi Fora site, and publishes papers on paleoanthropological topics. He is also the editor of the Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution.”

If you learned something from this episode, or especially if you enjoyed it, be sure to like, subscribe, and share to support this Open Access, free Human Origins resource. The more we collectively know about our past, the more prepared we can be to create a bright future. Remember, there is always more to learn!

A new way of Analyzing Cave Art, Hominins in Europe, and Massive Hand Axes in Kent!

https://www.podbean.com/media/share/pb-t4596-148e348

Learn about:

1. How changing the way we look at rock art reveals so much more: https://phys.org/news/2023-08-topographical-elements-paleolithic-art-revealed.html

2. Hominins Evolved in Europe?: https://phys.org/news/2023-08-ancient-ape-trkiye-story-human.html

3. Massive 300,000-year-old Hand Axes Found in Kent: https://scitechdaily.com/scientists-discover-300000-year-old-giant-handaxe-in-rare-ice-age-site/

CaveArt 101 Season Two Premieres Tomorrow!

I have exciting news! #CaveArt101 returns tomorrow with Season Two!

Be sure to catch up on season one here:

#CaveArt #Paleoanthropology #Humans #Culture #Art #MindintheCave #AncientMinds #SeasonTwo #WOPA

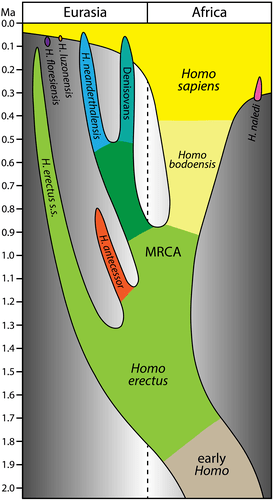

Understanding the ‘Muddle in the Middle’-Hominins from the Pleistocene-Guest Post by Mekhi

Introduction

Throughout the history of our evolution, few times have confused anthropologists more than the middle to late Pleistocene epoch. This time, from about 1 million years ago to 10,000 years ago, saw the emergence of our own species, along with our closest relatives, Neanderthals and the Denisovans. Sites from throughout Africa and into Europe give hints to our common ancestor with these other species, along with the origins of our own species, but perplexing morphologies in the fossil specimens make this time very confusing. Because of this, anthropologists have given this time the nickname, the ‘Muddle in the Middle’.

From this time at the end of the Pleistocene, there are plenty of fossil hominins. Fossils have been found all throughout Africa, Europe, and even as far into Asia. It is not a lack of fossils that makes this period of time confusing, rather the morphologies seen within the fossils. Many fossils have very similar traits to one another, making it difficult to decipher what specimens belong to what species. To make it worse, the geography and locations of these fossils makes it more confusing.

This time raises 3 main questions. First off, who was the common ancestor of us and our evolutionary cousins? Secondly, where did the Neanderthals even come from? And thirdly, and perhaps most important, where did we, Homo sapiens, come from? Though there is certainly no clear picture (at least, not yet), by examining all the fossils and evidence, we can get a decent understanding of what was happening in the infamous ‘Muddle in the Middle’.

Who was our Common Ancestor?

There are several species which could possibly be the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) between us and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). The most commonly accepted species is Homo heidelbergensis, but there is little agreement on what fossils are and are not this species.

Homo heidelbergensis is a mid-late Pleistocene hominin which lived about 600,000-300,000 years ago. This species shared several traits with modern humans (Homo sapiens), but was also very different. This species had larger jaws, teeth and face, particularly in terms of their brow ridges and frontal sinus. Virtual reconstructions of what the MRCA should look like match the morphology seen in Homo heidelbergensis, giving more support to the idea that this species, or something like it, is the common ancestor.

Fossils attributed to this species are found all throughout Africa and Europe. Specimens of Homo heidelbergensis from Africa, such as the Broken Hill skull (Kabwe 1) have been placed under the species name “Homo rhodesiensis”, though this taxa is not typically used. Other fossils from Europe may represent European H. heidelbergensis, but also might represent early, or ‘proto’ Neanderthals. One site in particular, in Spain, has provided many fossils from and can give great insight to understanding this mysterious time.

Found in Atapuerca, Spain, the Sima de los Huesos (“pit of bones”) site possesses many fossil hominins attributed to Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis. This site contains 12 stratolithographic chambers, only one of which (LU-6), contains hominin remains, along with other animal remains, such as bears (Family: Ursidae).

In this site, close to 8,000 fossil hominins have been found and excavated, making up roughly 30 individuals. Many of the specimens, such as the cranial specimen Atapuerca 5, have been attributed to Homo heidelbergensis, but resemble Neanderthals greatly in their morphology. This is seen especially in the dental remains from this site, of which there are over 30.

These teeth give great insight to the origins of Neanderthals. If these teeth do indeed belong to Homo heidelbergensis, it may support the idea that this species was only ancestral to Neanderthals, and may represent an early Neanderthal lineage.

Another species, also from Spain, may represent the common ancestor as well, Homo antecessor.

Homo antecessor is a species of late Pleistocene hominin which lived in Spain from 1.2 million-800,000 years ago. Found in Gran Dolina Cave, in Atapuerca, this species is the oldest known hominin from western and central Europe, giving clues to when humans first reached this area. This species lines up with the idea that humans migrated to Europe in several sporadic migrations/waves, with some of the oldest evidence of human habitation from Europe being stone tools dating to 1.2 million years ago. These tools suggest that humans adapted to the new European environments by improving their tools.

Homo antecessor is sometimes considered to be early European Homo heidelbergensis, and was once considered to be the common ancestor of us and Neanderthals, but it is no longer typically thought to be that. Instead, this species is thought to be a sister species to H. heidelbergensis descending from Homo ergaster in Africa.

Throughout the years, many of the Pleistocene hominin fossils from across Europe and Africa and even into Asia have been given different species names, such as Homo capanensis, Homo mauritanicus, and Homo helmei. However, recently, a new species was suggested in an attempt to clear up the muddle in the middle.

Homo bodoensis

Named Homo bodoensis, this new species would have a geographical range of parts of Africa and Europe, possibly representing the MRCA. Homo bodoesnsis is composed of African specimens of Homo heidelbergensis along with some European specimens, while other European specimens which more closely resemble Neanderthals, such as the ones from Sima de los Huesos, were grouped in under Homo neanderthalensis, as early Neanderthals.

Homo bodoensis is not widely accepted however, as many anthropologists believe that this could have been done but still under Homo heidelbergensis, saying that there is no need for an entirely new species.

No matter what species name you use, the fossils clearly show the origins of Neanderthals and our shared common ancestor with them. However, it does little for the origins of our own species, Homo sapiens.

Origins of Homo sapiens

The origins of our own lineage is one of the most interesting and important parts of this topic. Our species most likely arose out of Africa, though some have suggested we evolved in southwest Asia. Early fossils of Homo sapiens from Africa, though rare, show a lack of mosaic traits which is what would be expected in the LCA. Fossils such as Omo Kibish 1, Herto 1, and Herto 2, give further support to the idea that we arose in Africa, as they share a significant amount of derived traits with modern humans, and are likely some of the earliest known specimens of our own species.

Fossils of early Homo sapiens have been found from all throughout Africa, such as Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, and Florisbad, in South Africa. The oldest fossil of our species, known as Jebel Irhoud, suggests that Homo sapiens most likely evolved around 300,000 years ago.

The earliest Homo sapiens are referred to as ‘anatomically archaic’, and were morphologically different compared to anatomically modern Homo sapiens. They had larger brow ridges, a more extended skull, and overall looked more like earlier species such as Neanderthals. Archaic Homo sapiens existed from 300,000 to 160,000 years ago, when modern Homo sapiens took over. It wasn’t a sudden and quick transition however, as fossils show a chronological overlapping range in the variation of the two.

The Full Story

600,000 years ago in southern Africa, a new hominin species arose from Homo ergaster (African Homo erectus). This species, known as Homo heidelbergensis/Homo bodoensis, possessed many ancestral traits, such as a large extended skull, large teeth, large brow ridges, and a large frontal sinus, but also possessed with many derived traits, such as a more orthognathic face and a large frontal cortex.

One population of this new species migrated out of Africa, where it encountered another species which also evolved from Homo ergaster, Homo antecessor, in Spain. Populations of this group out of Africa stayed in Europe, where they would give rise to Neanderthals, while other populations would move farther east, and would become our other cousins, the Denisovans.

Homo heidelbergensis which remained in Africa would give rise to our own species, Homo sapiens. We would spread throughout Africa, then throughout the world, where we would encounter, interact with, breed with, and live with other human species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, until, by 40,000 years ago, we were the only ones left.

Conclusion

The story of our evolution is one of the most extensively researched fields of science. The combination of fossil and genetic evidence gives a great understanding of our evolutionary past, but it isn’t always so clear. The mid-late Pleistocene is one such time. There are many hominin fossils from this time, but the confusing and mixed morphology makes it very difficult to identify and classify them into different species. Fossils from the Sima de los Huesos site in Spain are especially confusing.

Many different species names have been proposed for certain fossils to clear things up, such as Homo heidelbergensis, Homo bodoensis, Homo capanensis, Homo mauritanicus, and Homo helmei, but there is little agreement on what species are valid or not, and this usually only confuses things more. Further research and discoveries, such as new fossils and genetic evidence are our best hope to resolve this confusing time.

Sources

- Fran, Dorey. “Homo heidelbergensis”. The Australian Museum, 28-06-21, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-heidelbergensis/

- Godhino, M. R., Fitton, C. L., Toro-Ibacache, V., Stringer, B. C., Lacruz, S. R., Bromage, G. T., O’Higgins, P. (2018). The biting performance of Homo sapiens and Homo heidelbergensis. Journal of Human Evolution, 118, 56-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.02.010

- Godhino, M. R., O’Higgins, P. (2017). The biomechanical significance of the frontal sinus in Kabwe 1 (Homo heidelbergensis). Journal of Human Evolution, 114, 141-153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.10.007

- Stringer, C. (2012). The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908). Evolutionary Anthropology, 21(3), 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21311

- Perner, J., Esken, F. (2015). Evolution of human cooperation in Homo heidelbergensis: Teleology versus mentalism. Developmental Review, 38, 69-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2015.07.005

- “Kabwe 1”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/kabwe-1

- Mounier, A., Marchal, F., Condemi, S. (2009). Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible. Journal of Human Evolution, 56(3), 219-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.12.006

- Czarnetzki, A., Jakob, T., Pusch, M. C. (2003). Paleopathological and variant conditions of the Homo heidelbergensis type specimen (Mauer, Germany). Journal of Human Evolution. 44(4), 479-495, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2484(03)00029-0

- “Florisbad”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/florisbad

- Curnoe, D., Brink, J. (2010). Evidence of pathological conditions in the Florisbad cranium. Journal of Human Evolution, 59(5), 504-513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.06.003

- Gracia-Téllez, A., Arsuaga, L, J., Martínez, I., Martín-Francés, L., Martinón-Torres, M., Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Bonmatí, A., Lira, J. (2012). Orofacial pathology in Homo heidelbergensis: The case of Skull 5 from the Sima de los Huesos site (Atapuerca, Spain). Quaternary International, 295(8), 83-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.005

- Sala, N., Pantoja-Pérez, A., Arsuaga, L. J., Pablos, A., Martínez, I. (2016). The Sima de los Huesos Crania: Analysis of the cranial breakage patterns. Journal of Archaeological Science, 72, 25-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.06.001

- Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Martínez I., Gracia-Téllez, A., Martinón-Torres, M., Arsuaga, L. J. (2020). The Sima de los Huesos Middle Pleistocene hominin site (Burgos, Spain). Estimation of the Number of Individuals. The Anatomical Record, 304(7), 1463-1477. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24551

- Carretero, J., García-González, R., Rodríguez, L., Arsuaga, L. J. (2023). Main anatomical characteristics of the hominin fossil humeri from the Sima de los Huesos Middle Pleistocene site, Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain: An update. The Anatomical Record. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.25194

- Martinón-Torres, M., Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Gómez-Robles, A., Prado-Simón, L., Arsuaga, L. J. (2011). Morphological description and comparison of the dental remains from Atapeurca-Sima de los Huersos site (Spain). Journal of Human Evolution, 62(1), 7-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.08.007

- Martínez, I., Arsuaga, L. J., Quam, R., Carretero, M. J., Gracia, A., Rodríguez, L. (2007). Human hyoid bones from the middle Pleistocene site of the Sima de los Huesos (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). Journal of Human Evolution. 54(1), 118-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.07.006

- Dorey, Fran. “Homo antecessor”. The Australian Museum, 17-12-19, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-antecessor/

- Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Martinón-Torres, M., Martín-Francés, L., Modesto-Mata, M., Martínez-de-Pinillos, M., García, C., Carbonell, E. (2017). Homo antecessor: The state of the art eighteen years later. Quaternary International, 433 (A)(17), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.049

- Barsky, D., Garcia, J., Martínez, K., Sala, R., Zaidner, Y., Carbonell, E, Toro-Moyano, I. (2013). Flake modification in European Early and Early-Middle Pleistocene stone tool assemblages. Quaternary International, 316(6), 140-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.05.024

- Harvati, K., Reyes-Centeno, H. (2022). Evolution of Homo in the Middle and Late Pleistocene. Journal of Human Evolution, 173, 103279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103279

- Mallegni, F., Carnieri, E., Bisconti, M., Tartarelli, G., Ricci, S., Biddittu, I., Segre, A. (2003). Homo cepranensis sp. nov. and the evolution of African-European Middle Pleistocene hominids. Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2(2), 153-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1631-0683(03)00015-0

- Roksandic, M., Radović, P., Wu, X., Bae, J. C. (2022). Resolving the ‘Muddle in the Middle’: The case for Homo bodoensis sp. nov. Evolutionary Anthropology. 31(1), 20-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21929

- “Bodo”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program. 08-30-22, https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/bodo

- Dorey, Fran. “Homo neanderthalensis-The Neanderthals”. The Australian Museum, 28-06-21. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-neanderthalensis/

- Stringer, C. (2016). The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 371(1698). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0237

- Bermúdez de Castro, M. J., Martinón-Torres, M. (2022). Quaternary International, 634(10), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.08.001

- Dorey, Fran. “Homo sapiens-modern humans”. The Australian Museum, 16-10-20, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/homo-sapiens-modern-humans/

- Callaway, E. (2017). Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species’ history. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2017.22114

- Dorey, Fran. “The Denisovans”. The Australian Museum, 20-04-20, https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/the-denisovans/

Call for Papers

Cambridge Journal of Human Behaviour: Call for Submissions (Vol. 2, Issue 2)

The Cambridge Journal of Human Behaviour (CJHB) is now calling for submissions! CJHB is an internationally registered, peer-reviewed journal that is interdisciplinary in nature and dedicated to publishing the exceptional work of undergraduates from across the globe.

We are a diamond open access journal, do not charge fees of any sort (subscription, processing, membership, or otherwise), and permit the author to re-publish their work elsewhere.

The deadline for the second issue of Volume 2 is 22nd September, 2023. Submissions are always open and can be submitted online via our website: www.cjhumanbehaviour.com

Specific details for submission:

- Dissertations, projects, and extended essays welcome

- 5,000 words maximum

- Any topic relating to human behaviour (archaeology, anthropology, psychology, biology, etc.)

- Interdisciplinary manuscripts strongly encouraged

- All work must have been completed during the course of a student’s undergraduate studies

- We are now also accepting book reviews

- Word limit: 1,500

- Reviews for books published in 2022 or later welcome

More detail can be found on our website! For reference, check out our past issues here: https://cjhumanbehaviour.com/publications/.

___________________

Any questions or concerns can be directed to myself Seth, at cjhumanbehaviour.ba.outreach@gmail.com.

Cold Snap in Europe Brought an End to Ancient Humans, Inter-Glacial Passage in the Americas, and Genetics and Peptides in Neanderthals and Denisovans!

https://www.podbean.com/media/share/pb-5ewyh-1484822

On this week’s episode, we discuss the following topics:

1. https://www.sci.news/othersciences/anthropology/paleoanthropology/early-pleistocene-extreme-glacial-cooling-12170.html

2. https://www.sci.news/medicine/neanderthal-denisovan-antimicrobial-peptides-12187.html

3. https://www.sci.news/medicine/neanderthal-denisovan-antimicrobial-peptides-12187.htm