Imagine stumbling upon an ancient skull hidden deep within a well—a secret preserved for nearly a century, now poised to rewrite the entire story of human evolution. This remarkable discovery from Harbin, China, known as the “Dragon Man” skull, has finally granted scientists and humanity our first comprehensive glimpse into the elusive Denisovan lineage (National Geographic, 2025).

An Extraordinary Fossil’s Journey

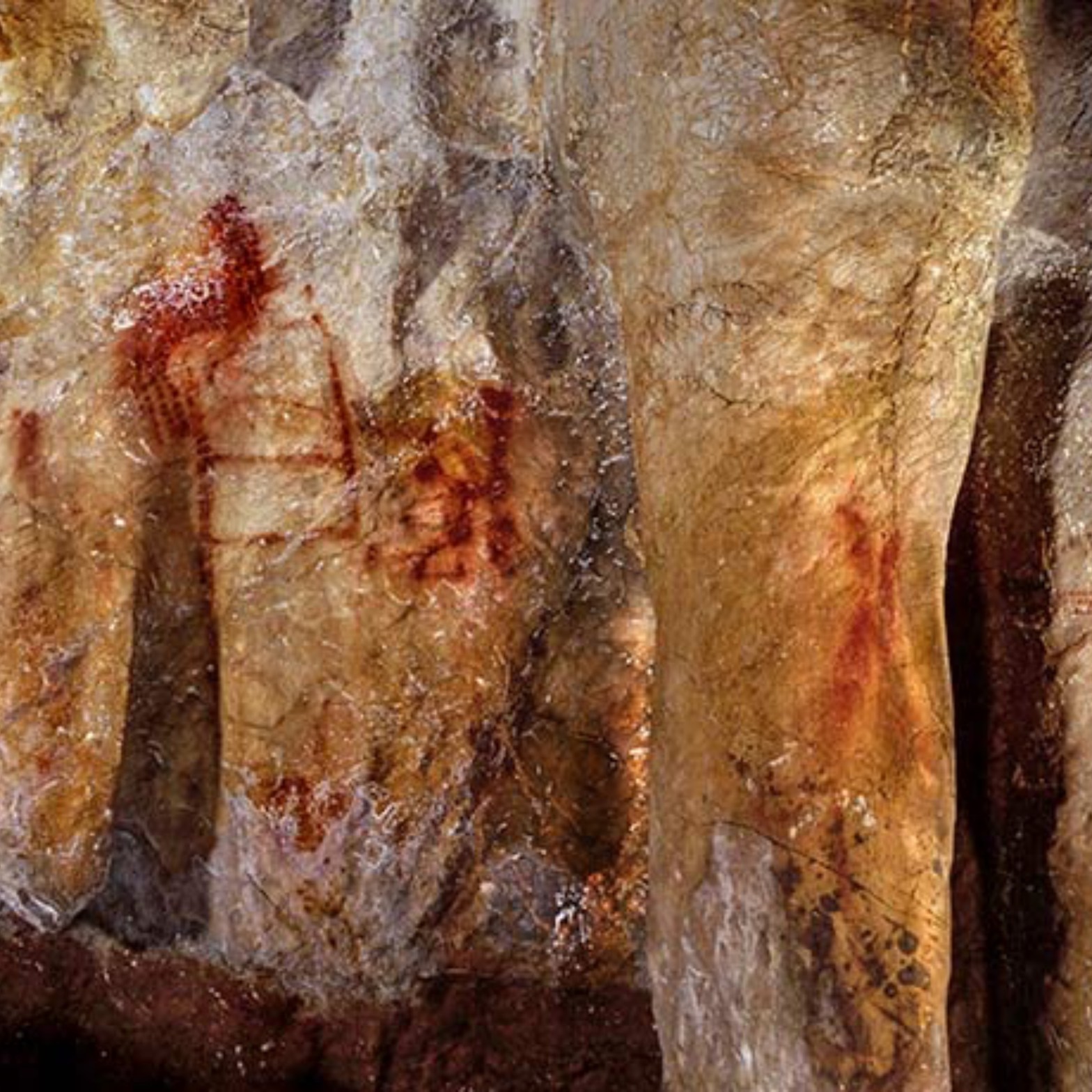

The fascinating saga begins dramatically in 1933, amid the tense atmosphere of Japanese occupation. A Chinese construction worker unearthed an exceptionally large and strikingly well-preserved skull near the Songhua River. Realizing its significance yet fearing it might fall into enemy hands, he courageously concealed the precious fossil at the bottom of a secluded well. Undetected and protected, this priceless relic remained hidden for over eight decades. In 2018, the worker’s descendants donated it to Hebei GEO University, revealing one of paleontology’s greatest treasures and initiating a profound shift in our understanding of human origins (ScienceAlert, 2025).

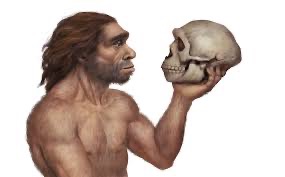

Dating back at least 146,000 years, the Dragon Man skull astounded researchers with its immaculate preservation and distinctive features. Its imposing brow ridge, broad nasal aperture, expansive eye sockets, and elongated braincase markedly differ from known ancient human fossils. The exceptional condition of the skull has provided scientists with an unparalleled opportunity to study, in intricate detail, the physical characteristics and evolutionary development of our ancient relatives (Live Science, 2025).

From New Species to Ancient Cousin

Initially, the scientific community considered the skull evidence of an entirely new human species, naming it Homo longi—or “Dragon Man”—in honor of the Dragon River region near the discovery site. This bold classification sparked vigorous debate, with some experts suggesting a potential link to the enigmatic Denisovans. Until now, Denisovans had only been known through small genetic fragments retrieved from bone pieces discovered in Siberia’s Denisova Cave (El País, 2025).

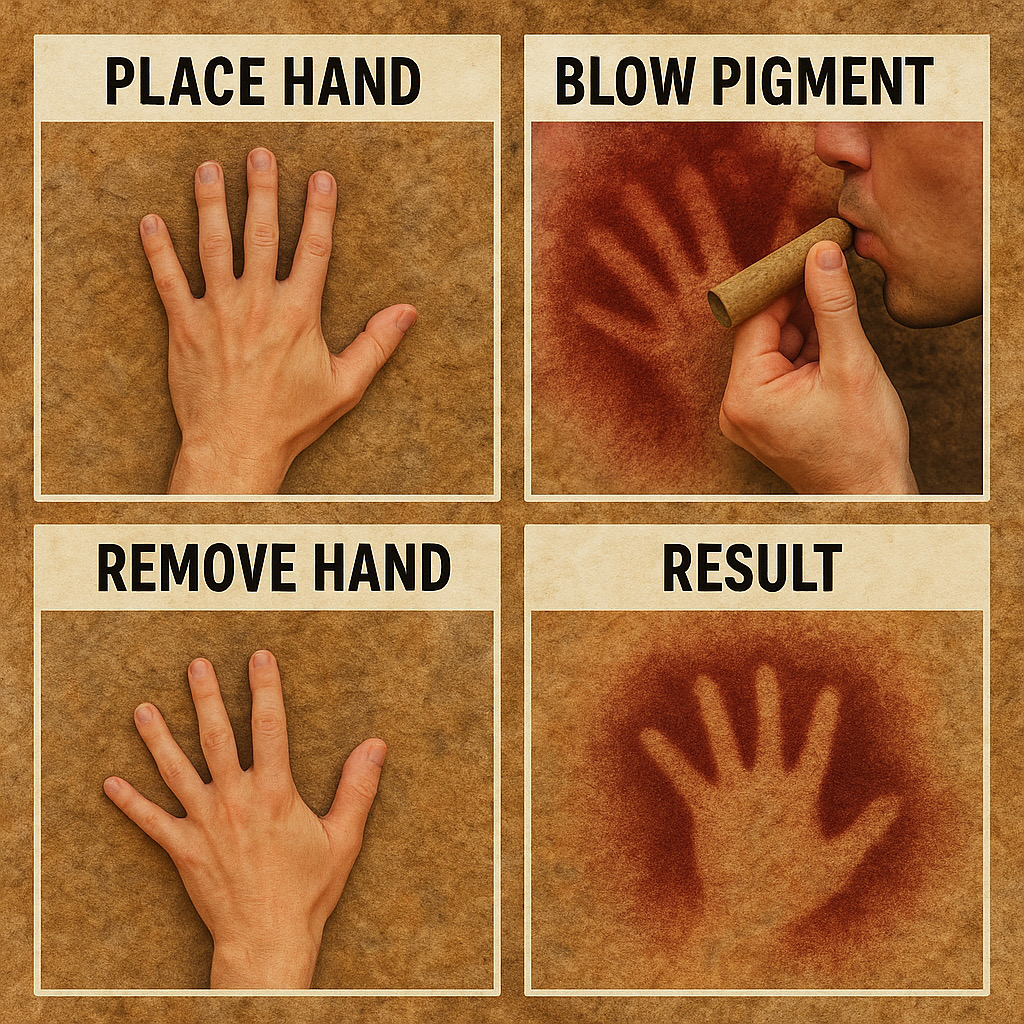

Molecular Magic: DNA Reveals the Truth

Resolving this scientific mystery required cutting-edge molecular technology. Paleogeneticist Qiaomei Fu, renowned for her groundbreaking work on Denisovan DNA from Siberian fragments, spearheaded the challenge. Fu’s team initially faced significant difficulties extracting viable genetic material directly from the skull’s bones and teeth. Their persistence was rewarded when they ingeniously retrieved mitochondrial DNA from dental calculus—ancient hardened plaque on the teeth. This innovative method decisively confirmed the Dragon Man’s Denisovan heritage, linking it genetically to an early Denisovan lineage previously recognized from Siberian fossil evidence (The New York Times, 2025).

Protein Analysis Solidifies the Connection

To further confirm their findings, researchers employed advanced paleoproteomic techniques, meticulously analyzing proteins preserved within the skull. This approach yielded an exceptionally detailed proteomic profile, uncovering distinct protein markers unique to Denisovans. With over 308,000 peptide matches, this protein analysis not only cemented the skull’s classification but also set a new standard in paleoproteomic studies, dramatically advancing our capacity to interpret ancient fossils (Popular Archaeology, 2025).

Putting a Face to Denisovans

For fifteen years, the Denisovans represented a profound enigma in human evolution—known only from sparse fossil fragments and incomplete genetic evidence. The discovery of the Dragon Man skull has transformed this narrative, finally allowing researchers to reconstruct the physical appearance of these ancient humans. Celebrated paleoartist John Gurche has skillfully produced vivid, lifelike reconstructions, depicting Denisovans as robust, resilient beings adapted to survive across diverse and challenging ancient Asian landscapes (Nature, 2025).

A New Perspective on Human Evolution

The Dragon Man discovery profoundly reshapes our perspective on ancient human migrations and adaptive strategies across Asia. Previously believed to be confined mainly to Siberia, Denisovans evidently occupied a much broader range and demonstrated impressive adaptability to varied environments. These insights help explain how Denisovan genetic material integrated into the DNA of contemporary Asian and Pacific Islander populations, conferring adaptations beneficial for life at high altitudes and survival in harsh climates (Science News, 2025).

Methodological Breakthroughs and Future Directions

Beyond its historical significance, the Dragon Man discovery marks substantial methodological advancements in paleogenetics and paleoproteomics. The successful extraction of genetic material from dental calculus opens new doors, enabling researchers to investigate numerous other fossils once deemed unsuitable for DNA analysis (Phys.org, 2025).

Although some methodological debates continue among experts, the scientific consensus robustly supports identifying the Dragon Man skull as Denisovan. Encouraged by these findings, researchers are reexamining previously discovered fossils throughout Asia, hopeful that more Denisovan specimens will emerge from obscurity (CNN, 2025).

A Landmark in Human Origins

More than merely a fascinating fossil, the Dragon Man skull symbolizes a transformative milestone in our exploration of human evolution. Hidden away for generations, this extraordinary relic now illuminates a critical missing chapter of our shared ancestral history.

As ongoing analysis progresses, the Dragon Man skull promises even deeper insights. It serves as an enduring testament to modern science’s potential to unveil ancient mysteries, significantly enriching our understanding of the diverse tapestry of human origins and the dynamic narrative of human evolutionary heritage.

References

CNN. (2025). ‘Dragon Man’ DNA revelation puts a face to a mysterious group of ancient humans. https://www.cnn.com/2025/06/18/science/dragon-man-skull-denisovan-dna-evidence

El País. (2025). Enigmatic ‘Dragon Man’ was not a new human species, but a Denisovan. https://english.elpais.com/science-tech/2025-06-18/enigmatic-dragon-man-was-not-a-new-human-species-but-a-denisovan.html

Live Science. (2025). 1st-ever Denisovan skull identified thanks to DNA analysis. https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/human-evolution/ancient-dragon-man-skull-from-china-isnt-what-we-thought

Nature. (2025). First-ever skull from ‘Denisovan’ reveals what ancient people looked like. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-01899-y

National Geographic. (2025). This is the first-ever confirmed skull of a Denisovan. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/controversial-dragon-man-skull-confirmed-to-be-a-denisovan