Implications for Human Evolution From Lice-Guest Post by Mekhi

Introduction

In the field of anthropology, scientists will look at anything if it can give clues about the story of our evolution. Fossils and genetics of ancient hominins are the most commonly studied things when researching paleoanthropology, but oftentimes, evidence can be found in small, unexpected things. One such thing, surprisingly, is lice.

The 3 species of lice which live off of humans have very interesting evolutionary histories and very interesting, and helpful implications for our evolution. Specifically, we can learn lots about the loss of fur and the later invention of clothing in human history, both of which are very important for understanding our own story.

The Biology of Lice

Lice are small insect ectoparasites which live off of the blood of their hosts, mainly placental mammals and birds. Lice have short lives and have a short life cycle, consisting of an egg, nymph, then adult. Each lice species is specific to their host species, and rarely inhabit multiple species.

They live alongside their hosts, and cospeciate into new species when their hosts due so, though they evolve at faster rates. Lice are very common and diverse, with roughly 550 recorded species. Human head lice are especially common, with prevalences up to 61%. When it comes to genetics, lice are also diploid, and possess 6 chromosomes (5 metacentric and 1 telocentric), and human body lice have the smallest genomes of any lice species.

Lice belong to the taxonomic order phthiraptera. This group is split into two subgroups, sucking lice (suborder anoplura), and the 3 suborders of chewing lice (amblycera, iIshnocera, and rhynchophthirina). Human lice are sucking lice, and are therefore in the suborder anoplura.

There are 3 kinds of lice that live off of humans, head, body, and pubic lice. All 3 have different habitats on the human body, and have different morphology and behavior to match it.

Body lice Body lice are known to cause several diseases, such as epidemic typhus, trench fever, and louse-born relapsing fever. Body lice are also hosts to the bacterial endosymbiont, Candidatus Riesia pediculicola, which can affect humans as well. These diseases have mostly diminished since the 1940s, with the advent of new treatments and medical practices, but are still present in some places. Body lice are common among homeless people in refugee camps, especially in Africa.

How Lice Relate to Our Evolution

The 3 types of lice that live on humans belong to 2 different genera. Head and body lice belong to the genus Pediculus, while pubic lice belong to the genus Pthirus. These 2 genera are sister taxa, and share a common ancestor going about 25 million years ago (25 mya). Head and body lice are also in the same species, Pediculus humanus. Head lice are in the subspecies Pediculus humanus capitis, and body lice are in the subspecies Pediculus humanus humanus.

Human head and body lice are contained within 6 mitochondrial clades, from A-F. Each clade affects different populations of modern, geographically unique humans. For example, clade F lice affects Amazonian peoples. Clade B lice seem to have arisen from Middle eastern people groups, but are found in many other groups as well, showing that later contact with other peoples, such as Native Americans, transferred the lice. Clade A is common throughout Thailand, and clade C is prevalent throughout Central, southern, and northeastern regions of this area. Genetic evidence shows a possible ancient connection between these people groups in South Asia. Other genetic evidence from lice suggests contact between archaic and modern humans.

Pediculus humanus shares their genus with chimpanzee lice, Pediculus schaefii, which is their closest relative, and the lice of platyrrhine (new world monkeys) (P. mjobergi). It is thought that these monkey’s lice were transmitted to them by the clade F Amazonian peoples who share the rainforest with them. Chimpanzee lice are very similar to human head and body lice, sharing 16/17 of their minichromosomes. Genetic studies show that the divergence of human head and body lice and chimpanzee lice took place around 6-7 mya, which lines up perfectly with the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees.This suggests that when humans and chimpanzees diverged, their lice diverged and evolved with them, adapting to their new hosts in a cospeciation event. Pediculus lice had genetic substitution rates 14% faster than both humans and chimpanzees, and therefore likely evolved and diverged at a faster rate.

Pubic lice however, share their genus with gorilla lice (Pthirus gorillae). These two groups seem to share a common ancestor with each other, going back 3-4 mya, long after the common ancestor between the two, showing that humans got pubic lice from gorillas somehow else. Gorilla lice were likely transferred to a species of australopith.

What We Can Learn

- Fur Loss

There are several hypotheses for why humans lost their fur. The not widely accepted aquatic ape hypothesis suggests that hominins would wade in bodies of water in the dry season to collect aquatic food sources, such as tubers and shellfish. Under this hypothesis, hominins lost their fur and developed a layer of fat to better adapt to the water.

Another hypothesis suggests that humans lost our fur in turn for more sweat glands. Support for this comes from the fact that humans have more sweat glands than any other mammal. Having lots of fur on our body would not go well with this, and thermoregulation is more efficient without it.

It is also possible that humans lost our fur because of the development of fire. With the development of fire and clothing, there was less of a need for fur to keep us warm at night.

One of the most common ideas is that as hominins began spending more time in the sun, leaving the trees as we became bipedal and becoming more active hunters in the open savannah, fur became much less advantageous. Less fur would reduce heat overload in the new environments hominins were exposed to. However, fur did not seem as big a problem to australopiths.

There were several assumptions made when this hypothesis was proposed however, such as that the temperatures australopiths lived in were at sea level (while they seemingly lived much more above sea level), australopiths were active all day (while they most likely were only active for about 16 hours a day), and that animals don’t take any thermal costs overnight (while in reality nightly temperatures in eastern Africa can get very low, and thus require more fur to stay warm).

It is more likely that major loss of fur occurred later, in later species of Homo, with exploitation of lower altitude habitats. Later species of genus Homo, such as Homo erectus, would have been much less affected, especially at night, due to their evident use of fire or even living in caves which also raises temperature at night. After a climate cooling event about 2.5 mya, hominins could have occupied much lower altitude habitats.

Because these hominins were much more active compared to australopiths (with Homo ergaster even being 50% more energetically efficient than Australopithecus), and were much more capable of traveling long distances, fur would be much less advantageous. Because Homo ergaster and later Homo erectus occupied lower altitude environments and migrated out of Africa very quickly, the loss of overall body hair would have been a useful adaptation for long distance migration into hotter open habitats.

The idea that australopiths lost their fur due to an introduction to a warmer environment ties fur loss to bipedalism, but there may be some valid ties between the two. One idea is that as hominins began losing their fur, their infants could less easily cling to their mothers, requiring them to stand up to be able to carry them. The hair loss that drove this change to bipedalism may have itself been driven by parasites such as ticks or lice. Losing their fur would have made it harder for parasitic organisms to cling to you.

Under this hypothesis, fur loss should have begun somewhere around 5-8 mya, when hominins began walking bipedally. The lack of evidence of tick-borne diseases in hominin paleoenvironments and the lack of a reason for why fur loss would be so beneficial may go against this idea however. Studying the evolution and divergence of human lice however, specifically pubic lice, may give more hints on why humans lost their fur.

Human pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) seem to have diverged from gorilla lice sometime around 3.3 mya. This is too recent for it to be a result of the human-gorilla common ancestor however. Instead of sharing a common ancestor, human pubic lice seem to be directly derived from gorilla lice, suggesting that hominins gained pubic lice from gorillas. This most likely happened due to hominins (most likely Australopithecus or Paranthropus) inhabiting the nests of gorillas, eating gorillas, or some other form of, possibly sexual contact.

As gorilla lice transitioned to living on human bodies, they may have been forced to reside and adapt to nesting in pubic hair once hominins began losing their fur, as it was the only place they could reside in. No other primates have pubic hair to the extent of humans, but it is beneficial in humans as it can show sexual maturity and trap pheromones. As humans lost our fur, pubic hair would have become more noticable and common, giving a more suitable home for pubic lice.

Genetic evidence suggests that the divergence of human pubic lice occured around 3.3 mya, meaning that humans began losing fur around that time and growing more prominent pubic hair, though it was likely not a drastic change yet at the time. Major loss of fur would come later with the rise of the genus Homo.

- The Origins of Clothing

During the late Pleistocene and into the Quaternary period, the earth saw dramatic rises and drops in temperatures. These changes in temperature resulted in a series of ice ages, including the last glacial maximum, the most recent major climate fluctuation, which started 27,000 years ago (27 kya).

With these drops in temperature, the development of clothing was crucial for the hominins in the region, specifically modern humans and Neanderthals. From 200,000-30,000 kya, Neanderthals lived through several of these glacial periods. The intricate tools and large brains of Neanderthals made them successful hunters, making furs from different animals more accessible.

Animals like mammoths, bears, musk oxen, and deer, would have provided very good material for hide coats which would have kept Neanderthals warm and dry. Animal hides such as those are not easy to study as they degrade quickly, but the oldest stone hide scrapers go back to about 780 kya. These hides may not necessarily have been used for clothing however, as they could have been used for shelter or other purposes.

Later Homo sapiens seem to have advanced off of the early clothing devised by Neanderthals, by creating more intricate systems. One of these systems was lacing furs together with hiding string. This allowed modern humans to create more complex body coverings, which could effectively cover the body, legs, and feet. One of the earliest forms of clothing which arose from this were tunics. Sewing needles were an important invention around this time that would have aided in this.

Early modern humans weren’t the only ones to use sewing needles however, as a sewing needle about 2 and 3-quarters an inch long was carved out of a bird bone by Denisovans, 50,000 kya. This suggests that Denisovans were producing more complex clothing, which would make sense considering that this population lived in Siberia, where clothing would be important for surviving the cold temperatures. This needle is one of the oldest known sewing needles, but after it sewing needles became very common in human populations throughout Eurasia and eventually into North America.

Other forms of body decoration aside from clothing have been used by hominins before clothing was ever a thing however. Individual talons belonging to white-tailed eagles have been found in the Krapina Neanderthal site, Croatia, with modifications that suggest they were used in bracelets or necklaces, from about 130,000 ya. This one of the many examples of early human jewelry.

Studying the divergence of human head and body lice can also give an idea of when humans began wearing clothes.

The body louse (Pediculus humanus humanus) exclusively nests and lays their eggs in clothes, so when humans began wearing clothes, it would have provided new nesting space, allowing them to diverge. The loss of fur in humans would have isolated Pediculus humanus to the head, and they would have further speciated with the introduction of a new habitat, clothing.

Genetic studies show that there was a genetic bottleneck event in Pediculus humanus, likely due to the loss of fur in humans, narrowing their habitat. A large portion of Pediculus humanus living on the head rapidly diversified to take up the newly introduced habitat, which is consistent with post-bottleneck expansions.

Other genetic evidence suggests that head and body lice diverged around 190 kya, and molecular clock analysis shows that at the youngest possible date for the evolution of body lice is 72 kya. This puts the origin of clothing in modern humans at about 190-72 kya.

Conclusion

Lice may be small, annoying, and downright harmful pests, but we can’t rule them out as an important part of our evolution because of this. Despite their small size and obscure, annoying nature, they are very important for understanding our evolutionary story. Two crucial aspects of human evolution, the loss of our fur, and when we began producing and wearing clothes are much more well understood now because of lice, however unexpected and underwhelming that may be.

Sources

- “Head Lice”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 09-11-19, https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/biology.html

- “Body Lice”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 09-12-19, https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/body/biology.html

- Bonilla, L. D., Durden, A. L., Eremeeva, E. M., Dasch, A. G. (2013). The Biology and Taxonomy of Head and Body Lice-Implications for Louse-Borne Disease Prevention. PLOS PATHOGENS, 9(11): e1003724. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003724

- Veracx, A., Raoult, D. (2012). Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends in Parasitology, 28(12), 563-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.003

- Dinulos, H. G., James. “Lice Infestation”. Merck Manuals, 2022.

https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/skin-disorders/parasitic-skin-infections/lice-infestation

- El-Showk, S. “Learning from Lice”. Accumulating Glitches, 09-28-15. https://www.nature.com/scitable/blog/accumulating-glitches/learning_from_lice/

- Reed, L. D., Light, E. J., Allen, M. J., Kirchman, J. J. (2007). Pair of lice lost or parasites regained: the evolutionary history of anthropoid primate lice. BMC Biology, 5, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-5-7

- Kang, S. J., Cho, Y., Kim, H. J., Kim, H. S., Yoo, S., Noh, S., Park, J., Yoon, S. K., Clark, M. J., Pittendrigh, R. B., Chun, J., Lee, H. S. (2015). Comparison of the genome profiles between head and body lice. Journal of Asia-Specific Entomology, 18(3), 377-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aspen.2015.04.010

- Herd, E. K., Barker, C. S., Shao, R. (2015). The mitochondrial genome of the chimpanzee louse, Pediculus schaefii: insights into the process of mitochondrial genome fragmentation in the blood-sucking lice of great apes. BMC Genomics, 16, 661. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1843-3

- Amanzougaghene, N., Fenollar, F., Raoult, D., Mediannikov, O. (2019). Where Are We At With Human Lice? A Review of the Current State of Knowledge. Frontiers, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00474

- Boutellis, A., Abi-Rached, L., Raoult, D. (2014). The origin and distribution of human lice in the world. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 23, 209-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2014.01.017

- Amanzougaghene, N., Fenollar, F., Davoust, B., Djossou, F., Ashfaq, M., Bitam, I., Raoult, D., Mediannikov, O. (2019). Mitochondrial diversity and phylogeographical analysis of Pediculus humanus reveals a new Amazonian clade “F”. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 70, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2019.02.006

- Amanzougaghene, N., Mumcouglu, Y. K., Fenollar, F., Alfi, S., Yesilyurt, G., Raoult, D., Mediannikov, O. (2016). High Ancient Genetic Diversity of Human Lice, Pediculus humanus, from Israel Reveals New Insights Into the Origin of Clade B Lice. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164659

- Phadungsaksawasdi, K., Sunantaraporn, S., Seatamanoch, N., Kongdachalert, S., Phumee, A., Kraivichian, K., Sawaswang, V., Payungporn, S., Brownell, S., Siriyasatien, P. (2021). Molecular analysis of mitochondrial cybt of Pediculus humanus capitis in Thailand revealed potential historical connection with South Asia. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257024

- Naddaf, R. S. (2018). Lice, Humans, and Microbes. Iran Biomed J, 22(5): 292-293. PMID: 29802698; PMCID: PMC6058184.

- Reed, L. D., Smith, S. V., Hammond, L. S., Rogers, R. A., Clayton, H. D. (2004). Genetic Analysis of Lice Supports Direct Contact between Modern and Archaic Humans. PLOS BIOLOGY. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020340

- Johnson, P. K., Allen, M. J., Olds, P. B., Mugisha, L., Reed, L. D., Paige, N. K., Pittendrgh, R. B. (2014). Rates of genomic divergence in humans, chimpanzees and their lice. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 181(1777). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2174

- Daley, Jason. “Why Did Humans Lose Their Fur?” Smithsonian Magazine. 12-11-18, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-did-humans-evolve-lose-fur-180970980/#

- Dávid-Barrett, T., Dunbar, M. I. R. (2016). Bipedality and hair loss in human evolution revisited: The impact of altitude and activity scheduling. Journal of Human Evolution, 94, 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.006

- Brown, G. J. (2021).Ticks, Hair Loss, and Non-Clinging Babies: A Novel Tick-Based Hypothesis for the Evolutionary Divergence of Humans and Chimpanzees. Life, 11(5), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11050435

- Light, E. J., Reed, L. D. (2008). Multigene analysis of phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of primate sucking lice (Phthiraptera: Anoplura). Molecular Phylogenetic and Evolution, 50(2), 376-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2008.10.023

- Keen, Cathy. “Human pubic lice acquired from gorillas gives evolutionary clues”. Florida Museum, 03,07, 2007. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/human-pubic-lice-acquired-from-gorillas-gives-evolutionary-clues/

- Weiss, A. R. (2009). Apes, lice and prehistory. Journal of Biology, 8, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/jbiol114

- Das, Monalisa. “Origin and History of Clothing”. Textile School, 02-14-22, https://www.textileschool.com/4639/origin-of-clothing/

- Davies, Bethan. “The Global Last Glacial Maximum”. Antarctic Glaciers, 06-15-17, https://www.antarcticglaciers.org/2017/06/global-last-glacial-maximum/

- 09-23-16. “Denisova Cave Yields a 50,000- year-Old Needle”. Archaeology Magazine, https://www.archaeology.org/news/4784-160823-denisova-cave-needle

- Shunkov, V. M., Fedorchenko, Y. A., Kozlikin, B. M., Derevianko, P. A. (2020). Initial Upper Paleolithic ornaments and formal bone tools from the East Chamber of Denisova Cave in the Russian Altai. Quaternary International, 559, 47-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.07.027

- d’Errico, F., Doyon, L., Zhang, Shuangquan, Z., Baumann, M., Lázničková-Galetová, M., Gao, X., Chen, F., Zhang, Y. (2018).The origin and evolution of sewing technologies in Eurasia and North America. Journal of Human Evolution, 125, 71-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.10.004

- Radovčić, D., Sršen, O. A., Radovčić, J., Frayer, W. D. (2015). Evidence for Neandertal Jewelry: Modified White-Tailed Eagle Claws at Krapina. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119802

- Zorich, Zach. “Neanderthal Necklace”. Archaeology Magazine, 07, 2015. https://www.archaeology.org/issues/182-1507/trenches/3366-trenches-neanderthal-eagle-talon-necklace

- Toups, A. M., Kitchen, A., Light, E. J., Reed, L. D. (2011). Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28 (1), 29-32. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msq234

- “What can lice tell us about human evolution”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-01-2020, https://humanorigins.si.edu/education/fun-facts/what-can-lice-tell-us-about-human-evolution

- Kittler, R., Kayser, M., Stoneking, M. (2003). Molecular Evolution of Pediculus humanus and the Origin of Clothing. Current Biology, 13(16), 1414-1417. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4

Homo Naledi…My Opinions

Premiering at 3 PM Pacific!

Up until this point, I have shared the information about Homo naledi as it comes out, I have given information on both sides, and I have given the facts, and even the interpretations.

Now, finally I am going to give you my opinion, based on all of the experts that I have talked to publicly, and privately. While I may be an armchair anthropologist (for now) I have direct 2nd had experience with dozens of involved individuals, my opinion is formed and based on a great a wide variety of information.

Let me know what you think in the comments below Be sure to like, share and subscribe for me!

Who Created the First Art? Homo Erectus?

So Google Bard got a major update today, and say what you want about AI, it’s not coming, it is here, and we might as well use it!

So I set it up to act as if it was a paleoanthropologist and asked it a few questions. Here is how it went:

I asked it who was the first creator of art-

Homo Erectus – The Cradle of Artistic Expression?

For decades, the realm of art and symbolism was considered the exclusive domain of Homo sapiens. However, recent discoveries have cast doubt on this long-held belief. Evidence suggests that our ancestors, Homo erectus, may have possessed a capacity for artistic expression previously thought unimaginable.

Here’s why Homo erectus could be responsible for the creation of art:

1. The Trinil Shell Engraving: In 2014, researchers discovered a half-million-year-old mussel shell bearing a complex zigzag pattern. This engraving, found on the Indonesian island of Java, predates by hundreds of thousands of years any previously known examples of art. While the exact purpose of the engraving remains unknown, its deliberate nature and geometric complexity suggest a symbolic or artistic intent.

2. Cognitive Abilities: Recent studies have revealed that Homo erectus possessed cognitive abilities far more sophisticated than previously assumed. They were capable of complex toolmaking, controlled fire, and used advanced hunting strategies. This suggests they possessed the cognitive capacity for abstract thinking and symbolic representation, essential prerequisites for artistic expression.

3. Ochre Use: Evidence suggests that Homo erectus used ochre, a naturally occurring pigment, at least 400,000 years ago. While the exact purpose of ochre use remains unclear, its potential applications include body decoration, marking tools, or even creating rudimentary art.

4. Engraved Bones: Although rare, a few engraved bones have been found associated with Homo erectus sites. While these markings are less complex than the Trinil shell engraving, their deliberate nature suggests an intention to communicate or represent something beyond the purely practical.

5. Cultural Practices: We know that Homo erectus engaged in complex cultural practices, including burial rituals and the use of symbolic objects. This suggests that they possessed a capacity for abstract thought and symbolic representation, which are fundamental to art creation.

6. Shared Ancestry: We share a common ancestor with Homo erectus, suggesting that the potential for artistic expression existed long before the emergence of Homo sapiens. This evolutionary continuity makes it plausible that Homo erectus may have engaged in rudimentary forms of artistic expression.

7. Expanding Definition of Art: Expanding our definition of art to encompass non-figurative and symbolic expressions may lead to the recognition of artistic endeavors in other hominin species. This shift in perspective opens up new possibilities for understanding the origins of human creativity.

While the debate surrounding Homo erectus and art remains ongoing, the evidence presented here suggests that they possessed the cognitive capabilities and cultural practices necessary for artistic expression. As we continue to uncover more evidence, the true extent of Homo erectus’ artistic potential will become increasingly clear.

In conclusion, while conclusive evidence remains elusive, the emerging data paints a compelling picture of Homo erectus as a species capable of artistic expression. Recognizing their potential in this realm challenges our understanding of human evolution and forces us to reconsider the origins of creativity.

What an interesting Discovery!

GIANT Hand Axe Discovered in Saudi Arabia!!!

Happy 99th Year Anniversary Taung Child! -Guest post by Mekhi

Introduction

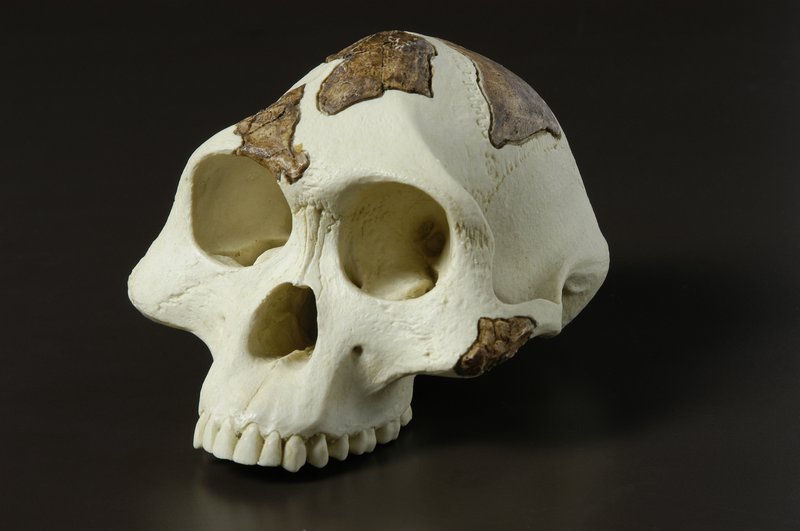

November 28th, 1924, exactly 99 years ago from today, a very significant hominin skull was unearthed near Taung, South Africa. On this day, a team of quarry workers uncovered the first described member of what would later be a very well represented hominin genus. This genus would be the genus Australopithecus, and the skull would be named the Taung Child, a juvenile member of the species Australopithecus africanus.

The Discovery

The Taung Child was found November 28th, 1924, in the Buxton-Lime Works quarry outside of Taung, South Africa. The physical location itself was a dissolution cavity, similar to a cave or sinkhole. The skull was surrounded by a carbonate-rich pedogenic sediment called a calcrete and breccia, a natural cement formed by water.

The skull was presented to anatomist Raymond Dart, who cleaned off the skull and researched it. The information of the skull would be published in 1925, and 3 photographs would be taken of Dart and the skull.

The Taung Child’s Significance

The Taung Child is the first member of the genus Australopithecus, the genus of bipedal ape that would give rise to the genus Homo of which all humans belong to. The name translates to ‘southern ape’ due to the location where the Taung child was found.

The species of the Taung Child is Australopithecus africanus. This species was closely related to the genus Homo, and lived from 3.2-2 million years ago.

What we Can Learn from the Taung Child

The skull was clearly that of a juvenile ape, but some features stood out as unique. The brain was much larger than that of other primates, like baboons and chimpanzees. The organization of the brain also suggested that the brain stem came down beneath the head, indicative of bipedal walking. Dart described the features of the skull as humanoid, and on the human lineage, supporting Darwin’s suggestions that humans arose in Africa.

The skull would be given the species name Australopithecus africanus, meaning southern ape of Africa, making it the first member of what would eventually be one of the most well known and well studied genera of extinct primate. The specimen itself would be identified as 3 years old, and given the name the Taung Child.

The child’s age was deduced by the presence of deciduous teeth, with its permanent molars growing in. On one of these permanent molars was the presence of linear enamel hypoplasia, an enamel defect associated with periods of malnutrition, illness or trauma. This suggests that the child underwent a period of stress or sickness around 2.5 years of age, although this is likely not what killed it.

One of the most significant aspects of the Taung Child is its endocast of its brain, a fossil imprint of the brain. The specimen’s endocast is very well preserved, and possesses many details. From this, it can be deduced that the Taung Child walked on its two legs due to the positioning of certain parts of the brain. Due to the young age of the Taung Child, the presence of an endocast is very important, as we can learn lots about the brain development of australopiths.

The Taung Child did not possess signs of postnatal brain development, such as a persistent metopic suture or an open anterior fontanelle. This suggests that Australopithecus had brain development more alike that of other apes rather than humans.

In modern humans, our brains grow to up to 70% their full size within a year after birth. In other apes however, this time is much longer. With the Taung child, we now know that this occurred later in the genus Homo, and australopiths had much slower brain development.

The rate of brain development from the Taung Child matches with adult members of the species, such as STS 71.

The Taung Child’s Death

One of the most interesting aspects of the Taung Child is the way it died. The Taung Child seems to have been killed by a predatory crowned eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus).

Talon marks are present in the orbits of the Taung Child’s skull, identical to the marks in the eye sockets of modern monkeys that have been hunted by the same species. Scratch marks are also present on the rest of the skull, including the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital bones.

It seems that the Taung Child was carried off by a predatory eagle, and was eaten in its nest, where the skull would fall to the ground and preserve, to be later uncovered 99 years ago today.

Conclusion

The Taung Child is one of the most important discoveries in the history of paleoanthropology. It was the first described member of the genus Australopithecus, a very fascinating and significant genus in our lineage. The amount of research done on this genus and everything we know about it all started with this skull from South Africa.

From this small skull, we are able to learn so much about the development of our ancestors’ brains, a difficult thing to learn about from fossils, and how our ancestors lived in their environments, and the dangers they faced. All this crucial information became accessible this day, 99 years ago.

Sources

- Tietz, Tabea, “The Discovery of the Taung Child”. SciHi Blog, 11-28-16. http://scihi.org/discovery-taung-child/

- Hopley, J. P., Herries, R. I. A., Baker, E. S., Kuhn, F. B., Mentor, C. G. (2013). Brief Communication: Beyond the South African cave paradigm—Australopithecus africanus from Plio–Pleistocene paleosol deposits at Taung. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 151(2), 316-324. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22272

- Strait, S. D. (2010). The Evolutionary History of the Australopiths. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 3, 341-352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-010-0249-6

- Dorey, Fran. “Australopithecus africanus”. The Australian Museum, 11-11-18. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/australopithecus-africanus/

- Brain, C. K., “Raymond Dart and our African Origins”. Uchicago Press (ND). https://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/284158_brain.html

- Štrkalj, G., Kaszycka, A. K. (2012). Shedding new light on an old mystery: Early photographs of the Taung Child. South African Journal of Science, 108, 11-12. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?pid=S0038-23532012000600019&script=sci_arttext

- “Taung Child”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/taung-child

- Lacruz, S. L., Rozzi, R. F., Bromage, C. T. (2005). Dental enamel hypoplasia, age at death, and weaning in the Taung child : research letter. South African Journal of Science, 101, 11, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC96314

- Holloway, L. R., Broadfield, C. D., Carlson, K. J. (2014). New high-resolution computed tomography data of the Taung partial cranium and endocast and their bearing on metopism and hominin brain evolution. PNAS, 111(36), 13022-13027. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1402905111

- Wits University, “Taung Child’s skull and brain not human-like in expansion”. Phys. org, 08-25-14. https://phys.org/news/2014-08-taung-child-skull-brain-human-like.html

- van Dyck, I. L., Morrow, M. E. (2017). Genetic control of postnatal human brain growth. Current Opinion in Neurology. 30(1), 114-124. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000405

- McNulty, P. K., Frost, R. S., Strait, S. D. (2006). Examining affinities of the Taung child by developmental simulation. 51(3), 274-296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.04.005

- “STS 71”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/sts-71

- Berger, R. L. (2006). Brief communication: Predatory bird damage to the Taung type-skull of Australopithecus africanus Dart 1925. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 131(2), 166-168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20415

- “Crowned Eagle”. eBird (ND). https://ebird.org/species/crheag1

- Berger, R. L., McGraw, S. W. (2007). Further evidence for eagle predation of, and feeding damage on, the Taung child. South African Journal of Science. 103, 11-12. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?pid=S0038-23532007000600013&script=sci_arttext

Happy 49th Year Anniversary Lucy!-Guest Post by Mekhi

Introduction

November 24th, 1974, exactly 49 years ago today, the world of paleoanthropology was changed forever. On this day, Donald Joahanson and his team discovered perhaps the most famous specimen of our evolutionary lineage, Lucy.

Lucy’s fame comes from the fact that she was the first of her species (Australopithecus afarensis), not because she’s the best specimen of this species, but for her time, she was very important, and would give us the first glimpse of the lives and biology of our ancestors.

Lucy’s Discovery

Lucy was discovered in 1974 in Hadar Ethiopia, by a team of paleoanthropologists made up of Donald Johanson, Tom Gray, Maurice Taieb, Alemayehu Asfaw, along with others. Johanson, who was 31 at the time, had recently gained his Ph.D and was a professor in Cleveland, Ohio. He had been to Ethiopia twice before, and even discovered a hominin knee joint on his second trip, the first hominin remains ever uncovered in the region. This discovery gave him hope for new discoveries this time.

Just as he hoped, he had more luck in 1974, when he discovered a partial skeleton of an australopith. He first spotted the proximal region of the ulna bone in the forearm. After some work, the team eventually uncovered many other fossils, including cranial fragments, a mandible, some ribs, vertebrae, both arms, parts of her pelvis (including her sacrum and innominate bone), and parts of her legs and feet. All the remains would make up about 40% of the full skeleton.

The specimen would be given the nickname of ‘Lucy’, named after the at the time popular Beatles song, “Lucy and the Sky of Diamonds”. She would be given the Ethiopian name Dinknesh, which is Amharic for “you are marvelous”. The fossils would be dated to about 3.2 million years old, and would be given the new species name, Australopithecus afarensis, meaning southern ape of Afar, named after the Afar region of Ethiopia she was discovered in.

Lucy’s Significance

Though Lucy wasn’t the first of the genus Australopithecus discovered, that honor goes to the Taung Child which was discovered 40 years earlier in 1924 by Raymond Dart, belonging to the species Australopithecus africanus, she was the first of the species Australopithecus afarensis to be discovered.

Since her discovery, several hundred other fossils have been found, making up many individuals, including Kadanuumuu, Selam, and the first family. Research from these fossils show that this species lived from about 3.9-2.8 mya, and lived throughout eastern Africa.

What we Can Learn from Lucy

Lucy’s size made Johanson believe that she was female, as in most primates, the females are much shorter. Computer reconstructions of Lucy’s femur gives it a length of of 277 mm, very close to previous estimates. Relating this to the rest of her body, Lucy seemed to have been about 104-106 cm tall, while males stood about 150 cm tall. This couldn’t have been because of her age however, as all her adult teeth had grown in by the time of her death.There has been some debate on Lucy’s sex, such as Häusler and Schmid (1995), but the larger consensus is that she was female. Along with her femur, Lucy also has a well preserved pelvis.

Lucy’s pelvis consists of a sacrum and innominate bone. Her sacrum had 5 fused sacral vertebrae just like modern humans, sharing the same morphology as well, such as an inferiorly-projecting cornua and a kidney-shaped inferior body articular surface. This morphology is also found in other related species, like Australopithecus sediba.

Compared to a chimpanzee and human pelvis, Lucy’s pelvis was more platypelloid, or flat. This has two implications for Australopithecus, 1. Bipedal locomotion would be much easier for them, and 2. Birth for this species would be slow and difficult, due to the pelvis being more narrow. Moving up from the pelvis, her vertebrae also hold some significance.

Lucy was found with 9 vertebrae. One vertebrae was uniquely worn and of a different texture however, and would later be reclassified as a vertebrae of Theropithecus darti, a large extinct species of modern Geladas, an old world monkey. This resulted in a reexamination of Lucy’s fossils, showing that the rest of her fossils did indeed belong to her.

This resulted in heavy scrutiny being placed on the whole hominin fossil record to make sure all the fossils were valid, ultimately being great for paleoanthropology. Overall, Lucy’s vertebrae were very human-like, and give some clues to how she walked, but aren’t useful for very much.

Lucy’s arms were very long, and had muscle attachment sites on her humerus, giving her very powerful arms great for climbing in trees. Lucy’s forearms also had the capacity for great elbow flexion, similar to chimpanzees, and had elbow extension similar to orangutans. This shows that Lucy was a great climber and certainly still spent time in the trees, but she was still clearly well adapted for terrestrial bipedalism.

Her femur was intermediate between chimpanzees and humans. Though her arms were well adapted for arboreal locomotion, her legs were well adapted to walking, with cortical thickness in the femoral neck which is useful for weight bearing. Digital muscular reconstructions of Lucy also show that she could walk bipedally. 36 muscles were recreated. The muscles in the leg were much larger than they are in humans, with the muscles in the thigh making up 74% of the mass of the leg compared to the 50% in humans.

These muscles would have made it very easy to walk on her two legs efficiently. Her legs and pelvis would have given her great ability to walk on her two legs, though she would still spend time in the trees, likely more at night to avoid nocturnal predators.

Lucy’s Death

The time Lucy spent in the trees may have ultimately been her demise. CT scans of Lucy’s fossils that were originally meant to study her locomotion showed impacted fractures and patterns of collapse. These fractures resembled that of a four-part proximal humeral fracture, which occurs when the head of the humerus is shoved into the shoulder joint, an event that usually happens when you brace yourself with your arms during a large fall or during a car crash. This suggested to the researchers that Lucy fell from some height, such as a tree.

Similar fractures were found throughout her body, in her ankle, knee, pelvis, and ribs. The researchers calculated that fractures like this would be the result of fall from a four story height at about 59 kilometers per hour. The fractures also had no sign of healing, suggesting that she was killed quickly by the supposed fall. Not everyone agrees with this idea however.

Others have suggested that the fractures were results of later geological processes after death. The fractures found in Lucy are also found in other animal fossils from the area, including the ones that would be spending no time in the trees at all, like antelope, gazelles, elephants, rhinos, and giraffes. This makes Lucy’s fall more controversial, and the true cause of her death unknown.

Conclusion

Though Lucy is by no means the best example of human evolution uncovered so far, she can still give us great information about our ancestors. From her size, the way she walked, her life, and her death, this 3.2 million year old australopith is still very significant, and was discovered exactly 49 years ago today.

Sources

- Schrein, C. M. (2015) Lucy: A marvelous specimen. Nature Education Knowledge 6(7):2. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/lucy-a-marvelous-specimen-135716086/

- “AL 288-1”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 06-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/al-288-1

- “Taung Child”. The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, 08-30-22. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/taung-child

- Dorey, Fran. “Australopithecus afarensis”. The Australian Museum, 14-05-21.https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/australopithecus-afarensis/

- Sylvester, D. A., Merkl, C. B., Mahfouz, R. M. (2008). Assessing A.L. 288-1 femur length using computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction. Journal of Human Evolution, 55(4), 665-671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.05.019

- Tague, G. R., Lovejoy, O. C. (1998). AL 288-1–Lucy or Lucifer: gender confusion in the Pliocene. Journal of Human Evolution, 35(1), 75-94. 10.1006/jhev.1998.0223

- Russo, A. G., Williams, A. S. (2014). “Lucy” (A.L. 288-1) had five sacral vertebrae. American Journal of Biological Anthropology. 156(2), 295-303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22642

- Rak, Y. (1991). Lucy’s pelvic anatomy: its role in bipedal gait. Journal of Human Evolution, 20(4), 283-290. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(91)90011-J

- Tague, G. R., Loveyjoy, O. C. (1986). The obstetric pelvis of A.L. 288-1 (Lucy). Journal of Human Evolution, 15(4), 237-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2484(86)80052-5

- Meyer, R. M., Williams, A. S., Smith, P. M., Sawyer, J. G. (2015). Lucy’s back: Reassessment of fossils associated with the A.L. 288-1 vertebral column. Journal of Human Evolution, 85, 174-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.05.007

- van Hilten, G. L. (2015). Why Lucy’s baboon bone is great for science (and evolution theory). Elsevier Connect, https://www.elsevier.com/connect/why-lucys-baboon-bone-is-great-for-science-and-evolution-theory

- Ibáñez-Gimeno, P. Manyosa, J., Galtés, I., Jordana, X., Moyà-Soyà, S., Malgosa, A. (2017). Forearm pronation efficiency in A.L. 288-1 (Australopithecus afarensis) and MH2 (Australopithecus sediba): Insights into their locomotor and manipulative habits. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 164(4), 788-800. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23319

- Ruff, B. C., Burgess, L. M., Ketcham, A. R., Kappelman, J. (2016). Limb Bone Structural Proportions and Locomotor Behavior in A.L. 288-1 (“Lucy”). PLoS ONE, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166095

- First hominin muscle reconstruction shows 3.2 million-year-old ‘Lucy’ could stand as erect as we do. Phys.org, 07-13-23. https://phys.org/news/2023-06-hominin-muscle-reconstruction-million-year-old-lucy.html

- Gibbons, Ann. “Did famed human ancestor ‘Lucy’ fall to her death?” Science, 08-29-16. https://www.science.org/content/article/did-famed-human-ancestor-lucy-fall-her-death

Is Homo naledi still Important?

Short answer, OF COURSE! It is a fascinating piece of the Human story.

Just because the new papers are being questioned, doesn’t make things wrong, it’s been the process so far. There used to be so much more to come!

Quick review of the new papers:

What does Google Bard, the collective mind of the internet, think?

“In 201(3), scientists announced the discovery of a new species of human ancestor, Homo naledi, in the Rising Star Cave in South Africa. The discovery was based on a remarkable collection of fossils, including skulls, jaws, teeth, and postcranial bones, representing at least 15 individuals. Homo naledi is characterized by a mosaic of features that are both primitive and derived, making it difficult to place it in the human family tree.

Anatomy and Morphology

Homo naledi is a small-bodied species, with adults standing about 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall. The braincase is small and relatively unspecialized, but the face is robust and the teeth are large. The postcranial skeleton is also relatively primitive, with features such as long arms and curved fingers that are reminiscent of chimpanzees.

Age and Environment

The fossils of Homo naledi are dated to between 236,000 and 335,000 years old, based on uranium-thorium dating of flowstones in the Rising Star Cave. This suggests that Homo naledi lived during the Middle Pleistocene, a time period that was characterized by significant environmental changes in Africa.

Behavior and Taphonomy

The Rising Star Cave is located in a remote and inaccessible part of the Cradle of Humankind, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in South Africa. The cave is deep and labyrinthine, and it is filled with sharp rocks and narrow passages. This suggests that Homo naledi was capable of navigating difficult environments.

The fossils of Homo naledi were found in a deep chamber of the cave, along with the remains of other animals such as hyenas, porcupines, and birds. This suggests that Homo naledi may have been preyed upon by other animals. However, it is also possible that Homo naledi actively deposited the bodies of dead animals in the cave.

Significance of the Discovery

The discovery of Homo naledi is significant for a number of reasons. First, it provides us with a new and important piece of the human evolutionary puzzle. Homo naledi is a close relative of our own species, and its discovery helps to fill in the gaps in our understanding of human evolution.

Second, the discovery of Homo naledi raises a number of important questions about the behavior and ecology of our early ancestors. Was Homo naledi capable of complex behaviors such as tool use or language? Was it a social animal? How did it interact with other species?

Third, the discovery of Homo naledi has important implications for our understanding of the diversity of human ancestors. For many years, scientists believed that there was a single linear path of human evolution, leading from our ape-like ancestors to modern humans. However, the discovery of Homo naledi suggests that human evolution was a much more complex and branching process.

Future Research

The discovery of Homo naledi is just the beginning of our understanding of this new species. Scientists are continuing to study the fossils and the Rising Star Cave in order to learn more about Homo naledi’s anatomy, behavior, and ecology. This research is likely to provide us with new and important insights into human evolution.”

Is Naledi a Fraud?

Science is about civil discourse. We learn from disagreements, and redoing the work over and over, ensuring we receive the same result across the board.

Science involves peers, review, and as I mentioned, reworking.

The naledi pre prints are just that, pre prints. The papers have not even come out yet. So let’s keep that in mind, and I can tell you there is a great deal more work going on at Rising Star, which I will of course be covering.

But in the meantime, we have what Berger et. al are purporting, and then this new paper, which is not the last of its kind, trust me there.

So with all of that in mind, what are your views on Riaing Star? Emotions, and dreams of what we want aside?

For a full detailed review of the new paper, as it’s behind a paywall, watch my video here:

“No Evidence” that #HomoNaledi buried their dead, made rock art, and lit fires new peer reviewed paper details…..https://worldofpaleoanthropology.org/2023/11/12/big-homo-naledi-updates-new-paperno-evidence/

Let’s have a discussion in the comments!

Big Homo Naledi Updates! New Paper!”No Evidence”!

We have some big developments in surrounding Homo naledi this week!

As many of you know, a few months ago there were some major, and I mean major announcements out of Rising Star from Dr. Berger and team. Announcements that would blow the top of the field of Paleoanthropology, and in many cases it did. Especially in the public eye.

But should it have?

Now that others have had a chance to look at the evidence, and come out with the first peer reviewed paper on the findings, things seem to be taking a different turn, but after the media blitz, will it even matter?

Tune in to find out!